YOU

Sometimes we can be surprised when these dynamics change and shift: an analysand explained recently how his sexual desire for his partner disappeared abruptly when he realised 'we were the same person

Welcome to the desert of the real!

If you desire the comfort of neat conclusions, you are lost in this space. Here, we indulge in the unsettling, the excessive, the paradoxes that define our existence.

So, if you have the means and value writing that both enriches and disturbs, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Below, a contribution from psychoanalyst Darian Leader. Read more of his writing at his Substack, McShrunk.

With the mayhem unleashed by Trump’s first round of trade tariffs on April 2nd, I was expecting to hear about little else in my practice. Most people I work with were directly or indirectly hit, with jobs, businesses and pensions all in the firing line. But in fact, hardly anyone spoke about the tariffs because they were too busy talking about ‘The White Lotus’: was the finale really justified? Who actually deserved to die? Who will return in the next series?

In my last Substack, taking a cue from the series, I looked at some of the links between identification and desire. We can want to be someone but have no sexual desire for them, just as we can desire someone sexually and want to be them at the same time. Sometimes we can be surprised when these dynamics change and shift: an analysand explained recently how his sexual desire for his partner disappeared abruptly when he realised “we were the same person”.

Freud famously distinguished between anaclitic and narcissistic choices here. When we are drawn to someone who we depend on, who perhaps nurtures us, we can love them as a child loves a parent. This is anaclitic choice, from the Greek anaklitos, to lean upon. Narcissistic choice, in contrast, is when we gravitate towards someone who resembles us, or who has qualities that we wish we had. Their image is part of our own self-image. We could think here of the many couples who look like each other, and love choices made on the grounds of sameness rather than difference.

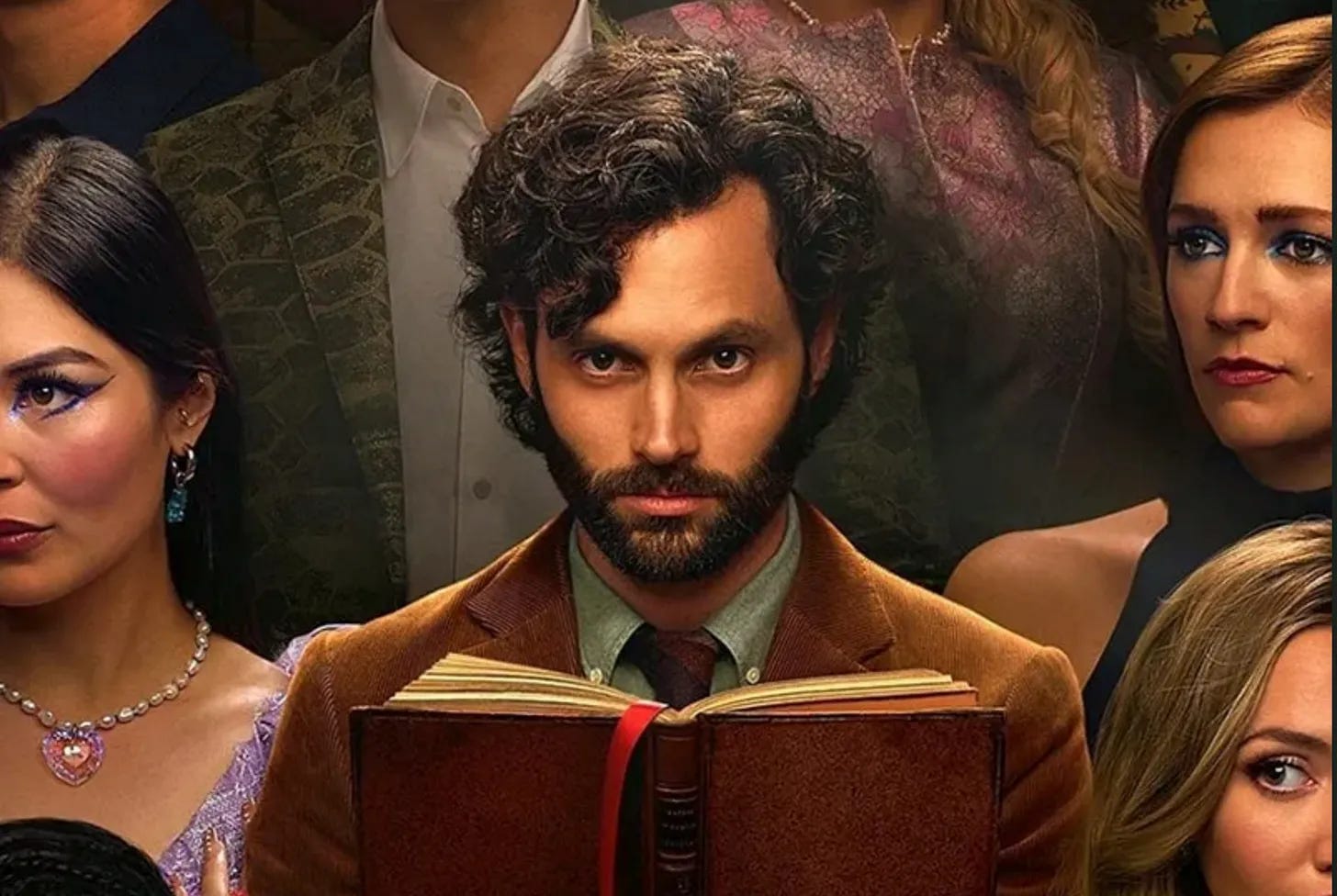

But Freud was not satisfied with this rather simplistic binary. We can love someone both anaclitically and narcissistically, and if another person has qualities we wish we had ourselves, this does not mean that they in any way resemble us. They might seem quite different, but they embody what we want to be, what we aspire to. After ‘The White Lotus’, these questions are perhaps explored most tenaciously in ‘You’, a Netflix series which had its final season and denouement drop this week.

Based on the books by Caroline Kepnes, ‘You’ tells the story of a serial killer Joe Goldberg, played with great gusto by Penn Badgely. Women fall in love with him, the love deepens, he knows that they are ‘the one’, but then doubt creeps in and he almost always ends up killing them. The love is presented as both the phantasy of his female victims, searching for their ‘knight’, and also of his own manipulative crafting of the relationships, as he elevates them to the status of the unique and sole object of his love. He makes his victims believe that they cannot live without him - or tries to.

The series shows nicely how one can lose oneself in the image of one’s beloved, as if their image quite literally replaces one’s own. The ‘You’ of the title replaces the ‘Me’, and each episode riffs deliberately on this ambiguity. ‘You’ refers to both Joe and the women he is in love with, as if they represent the missing part of himself. He describes searching for an image of himself, someone who will genuinely understand and accept him, and indeed, kill like he does. When they come that close to his own image of himself, the love crystallises and becomes overpowering.

As he evokes his own traumatic childhood, he seeks an echo in the women he loves, a comparable experience that would mean they share something profound with him. He is desperate that they are like him, the same as him. As his love escalates terrifyingly with each woman, they come to represent everything for him, as if the whole world is contracted to their unity. Nothing else exists. Or if it does, Joe has to get rid of it. In this suffocating universe, third parties are not tolerated.

He sees himself as the saviour and protector of his beloved, removing anyone that threatens them or who poses a risk to their togetherness. Murder is thus totally justified. He’ll kill for love, but the one thing that doesn’t fit into this romantic cocoon is his actual enjoyment of the act of killing. Guilt, altruism and sacrifice cannot absorb this horrifying excess, and it fractures the imaginary reciprocity he creates with the women he loves.

As he tries to force his partners into the straitjacket of his phantasy, their difference is denied. They must be like him. So the marker of otherness, of difference, the ‘You, means ‘Me’, what is the same, or at least what Joe hopes will be the same, and he will kill in order to make it so, to find the perfection of a complete, unbroken love. This means, of course, loving and being loved for everything that one is: flaws, weaknesses, and homicidal habits. Love is all inclusive.

In contrast, so many movies, TV series and books revolve around the opposite motif: the protagonist finds out that the person they know best - their husband, wife or lover – harbours a dark murderous secret, and this divides rather than unites them. When the secret is out, the guilty party usually tries to kill their partner.

The extraordinary ubiquity of this theme suggests that it may well be a part of all relationships. We can never know another person entirely, a part of the ‘You’ will always remain opaque, and we fill in the gaps by projecting homicidal, sexual or criminal intent. So in a way, we’d rather not know the whole ‘You’, or to put it more analytically, we’d rather not know the whole ‘Me’, so we project it into the ’You’.

As the sociologist Erving Goffman pointed out many years ago, every relationship is predicated on the fact that each party keeps something from the other - a shopping, gambling or masturbatory habit, for example. There is always something that is unspoken.

But what the many discovery narratives show is that when we start to pry and explore the unknown in our partner, we are less likely to imagine that they’ve bought new shoes than that they have a much darker and more dangerous secret, as if we need to project into that empty space something of our own unconscious phantasies.

Joe confronts his viewers with exactly this disturbing inversion in the final episode. Now that he’s in jail and convicted of his crimes, he receives letters from fans forgiving him and asking to be harmed by him, to be treated like his victims. These missives repeat the very structure of love that ran through the narrative: each person hopes they will be different, that they will be the one to tame the beast, to save the sinner.

It’s a fact that many incarcerated murderers receive letters like this, and even offers of marriage. During an earlier season of ‘You’, Badgely himself went onto social media to warn viewers not to idealise the character he plays, as the killer was becoming the object of love, sympathy and adoration across the internet.

As Joe’s last victim tells him, “We need a phantasy of someone like you to protect ourselves from the reality of someone like you”. And phantasies here can be far, far stronger than any reality.

Yet the ‘You’ ultimately refers not just to those who write letters to the imprisoned killer than to us, the viewers, who have continued watching five seasons of a show depicting coercion, manipulation and sustained violence against women.

We might hope that the punishment or killing of the criminal at the end of such stories is enough to exonerate us as viewers and allow us to get a good night’s sleep. But the fact that we watch the same story told again and again, night after night, suggests that we have to keep on replaying the problem and the solution, like applying a fresh plaster to a wound that never heals, a part of us that needs narratives like ‘You’ to keep us at the right distance from ourselves.

Darian Leader - McShrunk

I want to read more on this topic

Very sad to me that analysands were discussing White Lotus...