Welcome to the desert of the real.

Zizek Goads and Prods has been up and running for five months. My political writing is free, as is most of my philosophical and jokey pieces. Your subscriptions keep this page going, so if you have the means, and believe in paying for good writing, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The Birth of Fascism out of the Spirit of Beauty

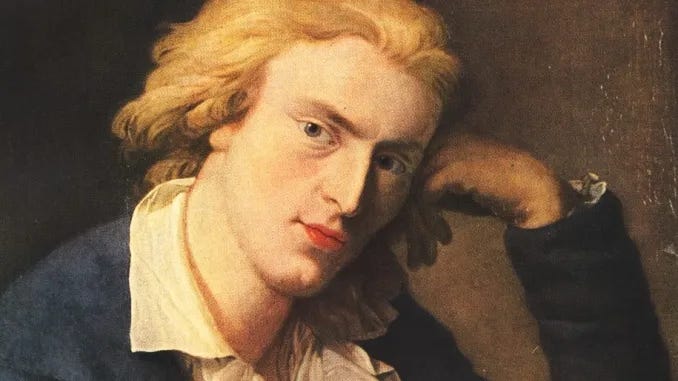

If we are in search of the origins of Fascism in modern thought, we should look into the work of one of the most celebrated poets of freedom, Friedrich Schiller. Following Marx, who said that the anatomy of man is the key to the anatomy of monkey, let’s begin at the end, with “The Song on the Bell,” the proto-Fascist Schiller offering his model of aestheticized politics as the way to overcome revolutionary violence. Then we’ll take a look at how Schiller arrived at this point, what antagonisms were obfuscated in this solution.

If there is a song that deserves to be publicly burned Goebbels-style, it is “The Song on the Bell.” Everything is in it, all the basic coordinates of a Fascist-style counterrevolution. It begins with the idealized image of a patriarchal family where man is a benevolent master who goes out, works, and takes risks, bringing home wealth, while the wife stays at home and wisely manages the household:

The man must go out / Into hostile life, / Must work and strive / And plant and produce, / Calculate, gather, / Must wager and risk, / To hunt for fortune. / There streams to him the endless gift, / The warehouse fills with precious goods, /

The rooms grow, the house expands. / And inside rules / The modest housewife, / The children's mother, / And reigns wisely / In the domestic circle, / And teaches the girls, / And guides the boy, / And stirs without end / The industrious hands, / And multiplies the gains / With orderly mind.

What enters then is the key metaphor of blazing fire, the source of productive energy—but only insofar as it is controlled by the man: if it runs out of control, it can bring horror and destruction:

Benevolent is the fire’s might, / If the man tames and watches it, / For what he builds, what he creates, / He owes to this heavenly power, / But terrible this heavenly power is, / If she, casting off her shackles, / Strides along on tracks her own / This free daughter of nature. / Beware when she is let loose / Growing without hindrance / Through the much populated by-streets / Rolls the monstrous blaze!

So where does this explosion come from? The feminization of fire as the “free daughter of nature” already indicates the answer: when, within the family, mother is no longer loyally subordinated to her husband, when “the tender bonds of the house are loosened”:

Alas! it is the loyal mother, / Which the black prince of shadows / Leads away from the arm of her husband, / Away from the children’s tender flock, / Which she bore him while in bloom, / Which she on her faithful breast / With motherly love watched grow— / Alas! the tender bonds of the house / Are loosened evermore, / She now lives in the land of shadows, / She who was the mother of the house, / Now her faithful reign is missing, / Her care watches no more, / In the orphaned place a strange one / Shall direct, lovelessly.

Another metaphoric level is then added: the glowing ore which liberates itself is first equated with the women liberated from family ties, and then the two are equated with the people (citizenry) breaking their chains and liberating themselves:

The master may break the mold / With knowing hand, if the time is right, / But beware when in fiery, spouting brooks / The glowing ore liberates itself! / Blindly raging, with the roar of thunder / It bursts the broken house, / And as out of the maw of Hell / It spews out, igniting destruction; / Where brute force rules mindlessly, / No design can emerge, / When the people liberate themselves, / Then wellbeing can’t thrive.

The political stakes are made explicit here: when “the citizenry, breaking its chains, frightfully seizes arms to help itself,” destructive violence explodes:

Freedom and Equality! one hears proclaimed, / The peaceful citizen is driven to arms, / The streets are filling, the halls, / The vigilante-bands are moving, / Then women change into hyenas / And make a plaything out of terror, / Though it twitches still, with panthers teeth, / They tear apart the enemy’s heart. / Nothing is holy any longer, loosened / Are all ties of righteousness, / The good gives room to bad, / And all vices freely rule. / Dangerous it is to wake the lion, / Ruinous is the tiger’s tooth, / But the most terrible of all the terrors, / That is the man when crazed. / Woe to those, who lend to the eternally-blind / Enlightenment’s heavenly torch! / It does not shine for him, it only can ignite / And puts to ashes towns and lands.

The French Revolution is thus feminized: the figure that embodies revolutionary terror is a woman changed into a madly laughing hyena. Plus, in the standard early liberal Enlightenment way, the full light of Reason should be constrained to the educated few: if Enlightenment’s heavenly torch is allowed to shine directly on the poor uneducated crowd who are condemned to eternal blindness, we get “the most terrible of all the terrors”. . . Schiller passes over the details of how one should crush this revolutionary explosion, and moves directly on to the idealized image of the collective production process which runs organically and harmoniously after order is restored:

Thousands of busy hands stir, / Help each other in happy union, / And in this fiery movement / All powers become known. / The master stirs and journeyman too / Within the holy protection of freedom. / Everyone enjoys his place, / Offering defiance to contemptors. / Work is the adornment of the burgher, / Blessing the reward for toil, / If dignity honors the king, / We are honored by industriousness of hands.

Although freedom is restored here, it is the protective freedom in which “everyone enjoys his place”—one is free insofar as one fully identifies with a specific place within the organic Whole. What such a vision prohibits is any kind of direct link between the individual and the universal dimension, bypassing the particular: the perfect utopian image of such freedom is the harmonious collaboration of individuals in an organically structured hierarchic Whole.

One should also note here that the same feminization of the revolutionary fury took place in the German conservative reaction to the October Revolution: we regularly encounter the myth of a wild Bolshevik woman, promiscuous and cruel, in Freikorps memoirs of the defenders of the Eastern borders of Germany after the Great War:

Anti-Bolshevism, anti-Semitism and a distinct hate for the other woman characterize these texts. The women of the enemy army are described as savage and uncivilized female warriors. These women took a very active part in the “butcheries,” thus wrote Georg Heinrich Hartman in his description of the time he spent in a Freikorps, published in 1929. The texts display an intense feeling of revulsion against Communist women, who, according to Klaus Theweleit’s psychoanalytical study of the Freikorps-literature, symbolized “a horror” that “had no name in the language of the soldierly man.” “At the hands of seductively smiling, gun-toting women” one received “the longest death. . . the most bitter and the most cruel which one could suffer,” wrote the Freikorps author Thor Goote. At the same time, these descriptions of the other women are ambivalent: the sensuality and the sexual prowess imputed to them are seductive and tempting. The way in which these descriptions are placed in the texts illuminates their function as a legitimization for the following violent excesses. Communist and Latvian women are desired but at the same time mutilated beyond recognition. The depictions of their executions are bloody, cruel and sadistic; they refer to the dangers of desire. Sexuality here uncovers the instable process of the construction of borders.[1]

Back to Schiller, is the ultimate laughing hyena not Caroline von Schlegel, the promiscuous Jacobin who wrote in 1799: “Yesterday at noon we almost fell from our chairs, we laughed so much at a poem by Schiller on the bell.”[2] No wonder she was referred to in the circle of Schiller’s friends as the “Dame Lucifer” or “the Evil [or Misfortune: das Übel]”. . . How did Schiller arrive at this point? Let’s move from this end point back to the beginning: in his first big success, The Robbers, Schiller already deals with the topic of the “Song on the Bell,” the danger of excessive unconstrained freedom. While he condemns the revolutionary attempt to “maintain law by lawlessness,” that is, to impose a new, just law through “illegitimate” change, Schiller symptomatically fails to raise the obvious question: But what if it is the existing law itself which maintains itself by lawlessness? What if the restoration of the “majesty of the law” restores also its lawless dark side? Furthermore, while, in his final speech, Karl, the play’s hero, generously offers himself as the exemplary victim ready to declare before all mankind how inviolable that majesty of the law is, he passes over in silence the true sacrificial offering, his love Amalia who convinces him to kill her. Although the logic of her demand seems rational (he cannot leave his gang and she cannot live without him), the killing remains a weird act branded by mysterious ambiguity, a true symptomal point of the play.[3] A woman is here an obstacle to men’s murderous gang, an agent of the stability of a home, not the revolutionary woman-hyena as in “The Song on the Bell”: revolutionary violence is here male bonding without women who stand for order and stability, not the murderous excess embodied in a free woman. The murder of the woman who disturbs male collaboration belongs to the antifeminist space of “The Song on the Bell”; it is precisely the moment Schiller passes over in silence in the poem, as the means to restore harmonious order—so it is as if the repressed of the poem returns here, in the opposite constellation where the woman should have been celebrated. . . Does this weird return not indicate that there is somethimg deeply wrong in the entire logic that underlies Schiller’s work? To cut a long story short, is the implication of the weird killing of the woman not that the lawless male bonding (in Robbers) is the obscene obverse of the noble male friendship and collaboration celebrated in “The Song on the Bell”? So how do we pass from the one to the other?

The answer is provided by Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” where, in a clear reversal of The Robbers, he asserts the brotherhood of man bonded by friendship as opposed to the gang of outlaws:

Be embraced, millions!

This kiss to the entire world!

Brothers—above the starry canopy

A loving father must dwell.

Whoever has had the great fortune,

To be a friend’s friend,

Whoever has won the love of a devoted wife,

Add his to our jubilation!

Indeed, whoever can call even one soul

His own on this earth!

And whoever was never able to must creep

The account of our misdeeds be destroyed!

Reconciled the entire world!

No wonder this poem provided the words for the anthem of the European Union: it describes the vision of global reconciliation with all debts written off—except those owed to big banks, as in the case of Greece, but the Greeks are then offered the choice of creeping away tearfully from the European circle. . . The difference from Robbers is that, in contrast to the gang led by a rebel against his father, her the circle of friends is sustained by the belief that “above the starry canopy a loving father must dwell.” We get here Schiller’s dream: a fraternal bond of friendship under the protective care of a benevolent father—an impossible combination, for sure, and this impossibility explodes in (is the theme of) Don Carlos, Schiller’s masterpiece which brings all these motifs together: friendship, love, political power and freedom.[4]

Don Carlos between Authority and Friendship

At the beginning of the play, the King Philip and his son don Carlos are rivals for the affections of Queen Elisabeth of Valois, but when Philip meets Carlos’s friend Marquis of Posa, he feels that he has found a true friend for the first time in his life. In a new love triangle, don Carlos and Philip are rivals for Posa’s love and friendship; however, Posa cares more about achieving political freedom in the rebellious Netherlands, and when his ruthlessly manipulative plan fails he sacrifices himself in order to save Carlos. Philip is affected more seriously by Posa’s betrayal than he is by Elisabeth’s presumed infidelity. At the end of act 4 the audience is informed by Count Lerma that “Der König hat / Geweint” (“The king has wept”) (lines 4464–65). In an ingenious cinematic detail, we never see Philip crying, it is just reported as an hors-champ detail, which makes it all the more effective. Later, in act 5, scene 9, after Marquis of Posa has died at his orders, Philip confesses that he loved him: “I loved him, loved him a lot. . . . He was my first love.” One should bear in mind here that, in a normally functioning monarchy, the problem of the humanization of authority (of how to provide the monarch with ordinary human features) doesn’t arise: for a true king, a patronizing friendship with selected courtiers is part of his image.[5]

It would be totally wrong to read this love in homosexual terms: the topic is that of friendship, friendship of equals in the sense of full mutual recognition and trust. The main tension of the play, its principal contradiction, to use the old Maoist term, is between (male) friendship and (political) power, while the topic of love remains at the level of comical intrigues; the king steals the bride from his son and then indulges in another affair, etc. Marcel Reich-Ranicki noted apropos of Don Carlos that one cannot take fully seriously a drama in which the plot relies on a love letter reaching a wrong addressee, and there are even three such letters in Schiller’s play (Carlos’s letter to the queen reaches Princess Eboli, the king’s letter to Eboli reaches Posa, Posa’s letter to the Dutch rebels is intercepted by the king’s police). Don Carlos who is the focus of love intrigues “might have been more successful as a comic figure.”[6] He is thoroughly immersed in the tensions of friendship and love, that is, he oscillates between two particular contents, which is why he doesn’t participate in any authentic tragic conflict. Posa is also outside the tragic conflict: he oscillates between Carlos and Philip, but at a purely tactical level, i.e., he has to choose whom to manipulate through friendship for his universal political cause. The only properly tragic character in the play is the king (as in Antigone where the only tragic character is Creon, not Antigone): Posa moves at the level of the universal, he is fully dedicated to his cause, don Carlos moves at the level of conflicting particulars, only the king is torn between the Universal and the Particular, State and friendship. The queen is also identified with the political cause (freedom for the Dutch), and her message to don Carlos is to pass from the Particular (his love for her) to the Universal (political freedom), so the ideal emancipatory couple would have been the one of Posa and the queen.

In contrast to this sometimes ridiculous melodramatic imbroglio, the play’s three crucial scenes all concern friendship and power. The first scene is the long conversation between the king and Posa in act 3. Posa tells him (twice) “Ich kann nicht Fürstendiener sein” (“I cannot be a servant of princes”), and it is precisely through this asserion of autonomy that he seduces Philip into friendship. Immediately using this friendship, Posa asks Philip to grant his subjects Gedankenfreiheit, the freedom of thought—he wants to use Philip immediately for his political cause. Predictably refusing this, Philip asks Posa to meet with Carlos and Elisabeth and find out their true intentions, enlisting him in his private affairs: “Marquis, so far / You've learned to know me as a king; but yet / You know me not as man.” Posa warns Philip that the price for being the king is that, since friendship requires mutual recognition of friends as equals, he has to remain alone in a friendless world: “Once degrade mankind, / And make him but a thing to play upon, / . . . You thus become / A thing apart, a species of your own. / This is the price you pay for being a god.” Furthermore, Posa reminds Philip that in a monarchy, not only can the king not have friends but friendship is thwarted even among his subjects: since they fear the authority, they are suspicious of each other and pushed into egotism, each possessed by fear and care for himself: “I dearly love mankind, / My gracious liege, but in a monarchy / I dare not love another than myself.” What Schiller stages here is the fundamental deadlock of the relationship between Master and Servant analyzed a decade later in the famous chapter of Hegel’s Phenomenology: the Servant’s recognition of the Master is worthless since the Servant is not recognized by the Master as an equal. Does this mean that Schiller is ready to renounce monarchy? As we have already seen, his solution is the utopia of the friendly bond of equals dominated by a loving father (Master) who “above the starry canopy must dwell.” In the famous declaration of his view of god, Posa further elaborates this vision:

Look round on all the glorious face of nature,

On freedom it is founded—see how rich,

Through freedom it has grown. The great Creator

Bestows upon the worm its drop of dew,

And gives free-will a triumph in abodes

Where lone corruption reigns. See your creation,

How small, how poor! The rustling of a leaf

Alarms the mighty lord of Christendom.

Each virtue makes you quake with fear. While he,

Not to disturb fair freedom’s blest appearance,

Permits the frightful ravages of evil

To waste his fair domains. The great Creator

We see not—he conceals himself within

His own eternal laws. The sceptic sees

Their operation, but beholds not Him.

“Wherefore a God!” he cries, “the world itself

Suffices for itself!” And Christian prayer

Ne’er praised him more than doth this blasphemy

Schiller’s formula of how to combine the reign of the Father-God with the freedom of His creatures is to render the Father invisible. This God is neither the Pascalean deus absconditus, the obscure withdrawn god whose impenetrable will causes anxiety among his subjects, nor the God of deism who just triggers the mechanism of the world and then lets it roll itself: Schiller’s God is acting all the time, but hidden behind his own laws. In contrast to the Christian god, a visible master who lives in fear, alarmed by the prospect that his subjects might misuse the freedom of their will, but at the same time allowing the evil to happen in the world in order to maintain the appearance of freedom, the true Creator lies concealed behind the immanent growth of creation, so that the more we are bewildered by the autonomous growth of the world, ignoring God, the more we praise God, his creativity. The political equivalent of this vision would be a benevolent paternal ruler who allows his subjects all their freedom, wisely steering their activity in order to prevent freedom to run amok and turn into a self-destructive fury. But does this idea work, theologically and politically?

With Posa himself, the advocate of this view, things quickly take a wrong turn. After his first plan of how to use his influence on the king fails, he decides to sacrifice himself: he writes a letter to William of Orange in Brussels, the leader of the Protestant rebellion there, knowing that it will be intercepted and brought to King Philip. He will be arrested, but suspicion will be diverted from Carlos who should escape to Netherlands and lead the rebellion. After Posa is shot down, he tells Carlos with his dying words to save himself by way of escaping. But instead of escaping, Carlos wants to confront his father courageously out of fidelity to Posa: when Philip and his noblemen arrive, Carlos blames his father for ordering Posa’s murder. (There is a nice ethical paradox at work here: in refusing to escape out of fidelity to Posa, don Carlos precisely betrays his friendship with Posa—he betrays the true point of Posa’s friendship/sacrifice out of friendship.) Carlos’s accusations are interrupted by the news that the people are rioting, clamoring to see him. Upon hearing the word “rebellion,” Philip is overcome by panic; he surrenders his royal insignia, faints, and is carried out.

When Philip divests himself of the royal insignia, he offers them to his son don Carlos whom he considers the leader of the rebellion, provoking him to take the insignia and become the new king, but the hysterical don Carlos is not ready or able to do it. In this act, Philip realizes his earlier declaration to Posa: “Marquis, so far / You’ve learned to know me as a king; but yet / You know me not as man.” Now everyone around him can see and know him as a man—but what, precisely, does one see? Recall the classic scene (so powerfully staged by Shakespeare in his Richard II) of the deposed king, a king deprived of his royal title: all of a sudden the charisma dissipates and we have in front of us a weak and confused man. . . But are we “really” just what we are, miserable individuals? What remains of Richard II after he is deprived of his insignia of royal power? Not an ordinary miserable person but a subject traumatized by the void of what he is now.[7] When he is deprived of his royal title, his bodily and psychic existence appear to him broken, inconsistent, lacking any firm ground or foundation, so that it is as if his symbolic insignia were not masking the miserable reality of a person to whom these insignia were attributed but the void or gap of subjectivity, of the Self irreducible to physical or psychic properties. And it is, of course, the same with Philip deprived of his insignia: we do not see an ordinary human being but, precisely, an extraordinary—crippled, panicked—human being. How, then, do the insignia of power transubstantiate our miserable bodily reality into the vehicle of another dimension, so that what we “really are” is magically transformed into a medium of power? The paradox is that it is only against the background of insignia (whatever they are, from those of a king to those of an office cleaner) that make a subject’s immediate reality visible as that of an “ordinary person”: how we perceive a person’s direct reality, the reality of his or her actual properties, is always-already mediated through the lenses of the insignia. If a king is crippled, it is not the same thing as a beggar who is crippled.

Back to Don Carlos: after the rebellion is crushed, the king survives, remains in power, but as a broken man and a broken king. What Philip loses when he renounces his insignia (and what he remains deprived of even after he later regains his insignia) is his main royal prerogative, his capacity to decide, to confer the performative dimension on his counselors’ advices, to make them acts. Hegel described this unique position of a king in clear terms:

In a fully organized state, it is only a question of the highest instance of formal decision, and all that is required in a monarch is someone to say “yes” and to dot the “i”; for the supreme office should be such that the particular character of its occupant is of no significance. . . . In a well-ordered monarchy, the objective aspect is solely the concern of the law, to which the monarch merely has to add his subjective “I will.”[8]

This “highest instance of formal decision,” this pronouncement of S1, a Master Signifier, which supplements the series of S2, of the knowledgeable proposals of his advisors and ministers, is what Philip is now deprived of, and this is why he sends for the Grand Inquisitor—not for advice about how to make the right decision but to decide instead of him. In the great confrontation between the broken king and the Inquisitor, the latter reprimands Philip for his leniency towards Posa which put in danger the very survival of monarchy. Philip asks him to decide Carlos’s fate and the Inquisitor decrees that Carlos must die.

This deeply disturbing dialogue between the king and the Inquisitor opens up upon a totally new terrifying, post-tragic, domain. The deadlock in which the King finds himself can be resolved only by the Inquisitor who enters almost as a deux ex machina, absent till now in the play.[i] The Inquisitor is blind but as such all-seeing and all-knowing—his blindness stands for his total ignorance of human passions and affairs, people are for him just numbers to be manipulated from a cold distance: “KING. I sought a human being. GRAND INQUISITOR. How! human beings! What are they to you? / Cyphers to count withal—no more! Alas! / . . . An earthly god must learn to bear the want / Of what may be denied him. When you whine / For sympathy is not the world your equal? / What rights should you possess above your equals?” The castrative dimension of supreme power is here clearly stated: the monarch “must learn to bear the want / Of what may be denied him.”

The Inquisitor knows in advance the answers to the questions he asks: “INQUISITOR. What was the reason for this murder? KING. ’Twas a fraud unparalleled—— INQUISITOR. I know it all.” Far from being the remainder of some dark past, the Inquisitor is the most modern figure in the play, he stands for the agency which takes over when the king’s authority disintegrates—in short, he stands for the big Other of the state bureaucracy, a pure superego-knowledge, not a crazy brutal Master. Apropos of Posa, the Inquisitor emphasizes precisely this complete knowledge: “All his life is noted / From its commencement to its sudden close, / In Santa Casa’s holy registers.” And when Posa is killed on the king’s orders, the Inquisitor deplores merely the spontaneous and brutal character of Posa’s death: Posa “is murdered—basely, foully murdered. / The blood that should so gloriously have flowed / To honor us has stained the assassin’s hand.” When he decides for the king, the Inquisitor does not simply appropriate the prerogative of the king, he is not a new S1 (Master), but an S2 without S1—the very definition of modern bureaucracy. Already the reasoning of the Inquisitor, the way he answers Philip’s queries, is subtle in an obscene way, a model case of senseless bureaucratic legalism. In in order to calm the king’s conscience troubled with how one can “justify / The bloody murder of one’s only son?”, the Inquisitor draws a weird parallel with God who sacrificed Christ, his own son, in order to redeem humanity: “To appease eternal justice God’s own Son / Expired upon the cross.” But if we draw this parallel to the end, what we get in Don Carlos is something like God asking Holy Spirit for permission/decision to deliver Christ to his death.

In contrast to the Inquisitor, the King-Master doesn’t “know it all,” but in an ambiguous way, leaving to others (his faithful servants) to do discretely the dirty job that has to be done but which cannot be admitted publicly. When, in the fall of 1586, Queen Elizabeth I was under pressure from her ministers to agree to the execution of Mary Stuart (the topic of another of Schiller’s plays), she replied to their petition with the famous “answer without an answer”: “If I should say I would not do what you request I might say perhaps more than I think. And if I should say I would do it, I might plunge myself into peril, whom you labor to preserve.”[10] The message was clear: she was not ready to say that she doesn’t want Mary executed since saying this would be saying “more than I think”—while she clearly wanted her dead, she did not want to publicly assume upon herself this act of judicial murder. The implicit message of her answer is thus a very clear one: if you are my true faithful servants, do this crime for me, kill her without making me responsible for her death, i.e., allowing me to protest my ignorance of the act and even punish some of you to sustain this false appearance.

Schiller versus Hegel

The true counterpart of the Inquisitor is thus not Philip but — who? None other than Posa. When the king is betrayed by Posa, he merely gets his own message back from him: he thought that, while he remains a king, Posa is now his equal, a friend to whom he is bound by mutual recognition, but he discovers that in the same way he looked down upon others, Posa now looks down upon him, just exploiting him for his own political purposes. And Posa is fully justified to ruthlessly manipulate his friendship with don Carlos and Philip in order to realize his political goal. Even when he sacrifices himself to save don Carlos (by way of sending a secret letter to the Dutch rebels he knows will be intercepted), he doesn’t do this out of friendship but again for a political purpose (to enable don Carlos to escape and lead the Dutch rebellion). There effectively is a weird parallel between Inquisitor and Posa: they are both cold functionaries fully dedicated to their cause, the only difference is that, while the Inquisitor is the functionary of the existing order, Posa is, to quote Reich-Ranicki, “the functionary of the revolution,” in short, a kind of proto-Leninist.

Schiller’s effort is to keep at a distance this friendless world whose two faces are the Inquisitor and Posa; he desperately tries to save friendship, although he is fully aware that the fraternal bond of friendship has to be discreetly controlled by a Master who has to remain friendless, as is made clear in a short poem “Die Freundschaft” (Friendship), written after Don Carlos and which recapitulates the king’s deadlock in the play, the need of an absolute Master for equal friends bound by mutual recognition. Here is the poem’s original version of 1782:

Friendless was the great world-master

Felt a lack—and so created spirits,

Blessed mirrors of his own blessedness

But the highest being still could find no equal.

From the chalice of the whole realm of souls

Foams up to him—infinitude.

Schiller describes here a lonely Creator who cannot overcome the gap that separates Him from his creation: the spirits He creates remain his own mirror images, shadowy insubstantial others, so He remains alone, caught in his own narcissistic game. Interestingly, the last two lines are quoted at the very conclusion of Hegel’s Phenomenology, but they are slightly changed; what is the meaning of this change? The standard approach to Hegel is that the Idea can afford extreme self-externalization since it is merely playing a game with itself, knowing full well that, at the end, it will safely return to itself, reappropriating its otherness. The difference between Hegel and Schiller is that Hegel fully endorses this view of the Absolute encountering only its own shadows and thus playing a narcissistic game with itself, while Schiller saw the deadlock of the Absolute: it cannot find any equal, so it remains lonely. . . But does this (standard) objection hold? Was Hegel not fully aware of the deadlock of a Master position? To clarify this point, let us take a look at the conclusion of Hegel’s Phenomenology, in which a dense description of Absolute Knowing is “sutured” by a quote from Schiller:

The goal, Absolute Knowing, or Spirit that knows itself as Spirit, has for its path the recollection of the Spirits as they are in themselves and as they accomplish the organization of their realm. Their preservation, regarded from the side of their free existence appearing in the form of contingency, is History; but regarded from the side of their. . . comprehended organization, it is the Science of Knowing in the sphere of appearance: the two together, comprehended History [begriffene Geschichte], form alike the inwardizing-memory [Erinnerung] and the Calvary of absolute Spirit, the actuality, truth, and certainty of its throne, without which it would be lifeless and alone. Only

from the chalice of this realm of spirits

foams forth for Him his infinitude

[aus dem Kelche dieses Geisterreiches

schäumt ihm seine Unendlichkeit].[11]

The last two lines are a (subtly transformed) quote from Friedrich Schiller’s poem—so what does Hegel achieve with theses changes? When Hegel quotes the same two lines again in his Philosophy of Religion, he supplements them with another poetic quote, the two lines from Goethe’s “An Suleika” (from West-östlicher Divan) where, apropos of the torment of the endless striving of love, Goethe writes: “Ought such torment to afflict us, / since it enhances our desire?”[12] The link between the two quotes is clear: what appears in the “chalice of this realm of spirits” is, as Hegel says two lines before, the “Calvary of absolute Spirit,” and insofar as the Spirit is able to recognize in this path of torment his own infinitude, traversing this path brings joy, that is, pleasure in pain itself.

If we read the infinite “foaming forth” from the chalice of spirits in this way, as the repetitive movement of the drive, then it also becomes clear how we can read it in a nonnarcissistic way, not as the philosophical covering up of the gap (conceded by Schiller) that separates the divine Absolute from the realm of finite spirits. In Hegel’s version, God is not just playing a game with Himself, pretending to lose Himself in externality while fully aware that He remains its master and creator: infinity is out there, and this “out there” is not a mere shadowy reflection of God’s infinite power. In short, the divine Absolute is itself caught up in a process it cannot control—the Calvary of the last paragraph of the Phenomenology is not the Calvary of finite beings who pay the price for the Absolute’s progress, but the Calvary of the Absolute itself. One should note how Hegel says here the exact opposite of the famous passage on the cunning of reason from his Philosophy of History:

The special interest of passion is thus inseparable from the active development of a general principle: for it is from the special and determinate and from its negation, that the Universal results. Particularity contends with its like, and some loss is involved in the issue. It is not the general idea that is implicated in opposition and combat, and that is exposed to danger. It remains in the background, untouched and uninjured. This may be called the cunning of reason,—that it sets the passions to work for itself, while that which develops its existence through such impulsion pays the penalty and suffers loss. For it is phenomenal being that is so treated, and of this, part is of no value, part is positive and real. The particular is for the most part of too trifling value as compared with the general: individuals are sacrificed and abandoned. The Idea pays the penalty of determinate existence and of corruptibility, not from itself, but from the passions of individuals.[13]

Here we get what we expect the “textbook Hegel” to say: Reason works as a hidden substantial power that realizes its goal by deftly exploiting individual passions; engaged individuals fight each other, and through their struggle the universal Idea actualizes itself. The conflict is thus limited to the domain of the particular, while the Idea “remains in the background, untouched and uninjured,” at peace with itself, as the calm of the true universality: subjects are reduced to instruments of historical substance. This standard teleology is, however, totally rejected by what Hegel sees as the fundamental lesson of Christianity: far from remaining “in the background, untouched and uninjured,” the Absolute itself pays the price, irretrievably sacrificing itself.

We should remember here that Schiller was the main proponent of the German aesthetic reaction to the French Revolution: his message was that, in order to avoid the destructive fury of the Terror, the revolution should occur with the rise of a new aesthetic sensibility, through the transformation of the state into an organic and beautiful Whole (Lacoue-Labarthe located the beginnings of Fascism in this aesthetic rejection of the Jacobin Terror).[14] Since Hegel clearly saw the necessity of the Terror, his reference to Schiller could be paraphrased as: only from the chalice of this revolutionary Terror foams forth the infinitude of spiritual freedom. (And, taking a step further, we can even propose a paraphrase concerning the relationship between Phenomenology and Logic: only from the chalice of phenomenology, which contains the Calvary of the Absolute Spirit, foams forth the infinitude of logic, pure logic.)

This brings us back to Schiller’s aestheticization of politics which should protect us from revolutionary terror: with regard to the French Revolution, he “expresses the wager of an entire generation: we don’t need that kind of revolution. Only through aesthetic revolution can we forestall the explosion of politics into terror. Only through beauty do we inch our way towards freedom.”[15] This is how Fascism begins—in contrast to Hegel who does not forestall explosions of terror but accepts the necessity of passing through it. In other words, Schiller—although he presents himself as the poet of freedom—effectively pleads for the restoration of a discreet, benevolent Master who can only prevent the explosion of politics into terror. There are two modes of “ugly” freedom that Schiller rejects: the destructive revolutionary freedom and the “mechanic” chaos of unorganic market relations where each individual pursues only egotist goals. They are perceived as the two sides of the same process which can be countered only through the aestheticization of politics. It is this aestheticization which renders Schiller blind to the new forms of domination which, already in his lifetime, began to replace the classic disposition of power which is sustained by symbolic castration.

The Self-Debased Authority

More precisely, what Schiller was not able to see is how contemporary authority is split into two: on one hand a pure blind knowledge (embodied in the Inquisitor), and on the other hand a friendly boss “like us,” with all ordinary human weaknesses—the necessity of this second figure is what Schiller couldn’t see. Philip is at the end of the drama not just playing castration in order to retain his full actual power, he really is broken and impotent—Schiller wasn’t yet able to imagine the figure of a master who rules through a display of his castration. The only “castration” he clearly saw was the alienation of the monarch who is unable to engage in authentic friendship.

Symbolic castration is the price to be paid for the exercise of power. How, precisely? One should begin by conceiving of phallus as a signifier—which means what? From the traditional rituals of investiture, we know the objects which not only “symbolize” power, but put the subject who acquires them into the position of effectively exercising power—if a king holds in his hands the scepter and wears the crown, his words will be taken as the words of a king. Such insignia are external, not part of my nature: I don them; I wear them in order to exert power. As such, they “castrate” me: they introduce a gap between what I immediately am and the function that I exercise (i.e., I am never fully at the level of my function). This is what the infamous “symbolic castration” means: not “castration as symbolic, as just symbolically enacted” (in the sense in which we say that, when I am deprived of something, I am “symbolically castrated”), but the castration which occurs by the very fact of me being caught in the symbolic order, assuming a symbolic mandate. Castration is the very gap between what I immediately am and the symbolic mandate which confers on me this “authority.” In this precise sense, far from being the opposite of power, it is synonymous with power; it is that which confers power on me. And one has to think of the phallus not as the organ which immediately expresses the vital force of my being, my virility, and so on, but, precisely, as such an insignia, as a mask which I put on in the same way a king or judge puts on his insignia—phallus is an “organ without a body” which I put on, which gets attached to my body, without ever becoming its “organic part,” namely, forever sticking out as its incoherent, excessive supplement.

However, this gap between the symbolic title (its insignia) and the miserable reality of the individual who bears this title tends to function today in a radically different way: it underwent a weird reversal noted by Badiou apropos of Jean Genet’s Balcon: “We encounter here an imaginary feature of democracy. Democracy means precisely that there are no costumes. Inequality no longer wears a costume/dress. There are dramatic, gigantic inequalities, but their laicization leaves them without a costume.”[16] On a simple descriptive level, this means that, in a democratic-egalitarian society, masters (those who exert power over others) no longer have to wear insignia or costumes that would performatively constitute them as bearers of power: they can dress and act “naturally” like everybody else, renouncing all dignity. The message of the way they dress and act is: “See, we are common people like you, with all weaknesses, fears, and limitations like everyone else!”—in short, their “castration” is no longer covered up by the splendor of their insignia but is openly displayed. However, this “honest” operation should in no way deceive us: for all their common appearance they continue to assert their full power, perhaps even more directly than the traditional master: “Let the image be castrated in all possible ways, while I can do more or less whatever I want. . . . In a strange reversal of the classic logic of castration (as a means to access symbolic power), we are dealing here with the castration of the symbolic (public) image as a means to execute and perpetuate limitless power.”[17]

Castration (the display of weakness) thus “becomes part of the public image,” but not in the simple and straightforward sense that it simply masks the actual exercise of ruthless power—the point is rather that this mask of castration is the very means (instrument, mode) of how power is exercised.[18] The mystification is here redoubled: beneath the gesture of demystification (“You see, I dropped all masks and costumes, I am an ordinary guy like you!”), the exercise of power (which is a symbolic fact, not a “real” property of its agent) remains intact. When confronted with a boss who talks and acts as an ordinary man, his subordinate would thus be fully justified in addressing him with a paraphrase of the well-known Marx Brothers phrase: “Why are you talking and acting as an ordinary man when you really are just an ordinary man?” (The paradox is that, if the agent of power were to put on the masks of insignia, this would not increase his power but undermine it, making it appear ridiculously pathetic.) The matrix of je sais bien mais quand même is here given a specific twist formulated by Zupančič: it is no longer just “I know very well that you are an ordinary weak guy like me, but I still accept you as a master,” it is rather something like “I know very well you are a miserable weak guy like me, and for that very reason I can continue to obey you like my master.” Knowledge is here not an obstacle to be suspended but a positive condition of the functioning of what it discloses in its gesture of “demystification.” The mystification persists not in spite of its denunciation but through it, because of it. (In a strictly homologous way, Freud demonstrates how repression can persist through the very knowledge [conscious awareness] of the repressed content—repression remains active even when we “know it all.”)

So, back to Don Carlos, Philip is at the end of the drama not just playing castration in order to retain his full actual power, he really is broken and impotent—Schiller wasn’t yet able to imagine the figure of a master who rules through a display of his castration. What he wasn’t able to imagine is the totally new link between authority and friendship that we can observe in today’s power figures: a Master who claims he is “our pal,” who renounces his insignia and presents himself as our equal friend while retaining all his authority with the help of this very self-debasement. In other words, what Schiller was not able to think is the reversal of the status of castration in the functioning of power: in the traditional power, castration that sustains it resides in the fact that the phallic insignia which provide power are decentered with regard to the subject; in contemporary power, the castration that sustains power is the very fact of being deprived of the insignia of power.

[1] Sandra Mass, “The ‘Volkskörper’ in Fear: Gender, Race and Sexuality in the Weimar Republic,” in New Dangerous Liasions: Discourses on Europe and Love in the Twentieth Century, ed. Luisa Passerini, Liliana Ellena, and Alexander Geppert (Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010), 233–50.

[2] Quoted from http://www.literaturkritik.de/public/rezension.php?rez_id=8062&ausgabe=200505.

[3] Incidentally, there is a similar weird turn in David Fincher’s putstanding thriller Seven in which John Doe, a religiously obsessed serial murderer, executes the plan of killing seven people each of whom is punished for one of the deadly sins. At the film’s end John Doe himself is shot by detective Mills who, out of anger, kills him because Doe killed his pregnant wife; Doe’s sin is envy (he envied Mills for his ordinary happy family life), and Mills’s sin is anger. . . but why then did Doe decapitate Mills’s wife? Her death clearly doesn’t fit the series: she committed no sin, she is killed just to awaken uncontrollable anger in Mills. We have here a temporal reversal: Mills is punished for something (anger) that explodes after he is punished for it, and is even triggered by this punishment. So it is as if woman’s death doesn’t count for itself, she can be killed just to punish her man.

[4] One should mention also Verdi’s Don Carlo, his absolute masterpiece where he comes very close to a Wagnerian musical drama, with almost no traditional arias—except the famous duo on friendship.

[5] We can also clearly see the difference between Philip’s search for a friend and Prince Hal’s friendship with Falstaff in Shakespeare: Prince Hal engages in this friendship for purely manipulative reasons and rejects Falstaff the moment he ascends the throne.

[6] Mark William Roche, Tragedy and Comedy (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998), 125.

[7] I rely here extensively on Alenka Zupančič, “Kostumografija moči” (manuscript in Slovene, July 2014).

[8] Quoted from Hegel's Philosophy of Right (marxists.org). If the king is only a formal point of decision—all the content is provided to him by his expert counselors, and he only has to sign his name—is there nonetheless a level at which he can act arbitrarily also at the level of content and not only confer the form of an abyssal decision onto a prepared content? Would such a level not be necessarily, by definition, illegal, a space in which the king not only can but is even expected to violate the law? Frank Ruda noted that there effectively is such a level: one of the prerogatives of the king is his right to clemency, to arbitrarily pardon criminals who were condemned by the law.

[9] It is well known that Dostoyevsky modeled his figure of the Grand Inquisitor in Brothers Karamazov on Schiller’s Inquisitor; however, one can immediately see the superiority of Schiller’s figure.

[10] Robert Hutchinson, Elizabeth’s Spy Master (London: Orion Books, 2006), 168.

[11] Quoted from Hegel - Phenomenology of Mind (marxists.org).

[12] Hegel, Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion, Oxford: Oxford University press 2007, p. 111–12.

[13] G. W. F. Hegel, Philosophy of History, available at www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/hi/.

[14] See Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Heidegger, Art and Politics (London: Blackwell, 1990).

[15] Rebecca Comay, “Hegel’s Last Words,” in The End of History, ed. A. E. Swiffen (London: Routledge, 2012), 234.

[16] Alain Badiou, Pornographie du temps présent (Paris: Fayard, 2013), 37.

[17] Alenka Zupančič, op.cit.

[18] Is then Jesus on the Cross not the ultimate castrated King/Authority, the one who exerts absolute power on behalf of his very “castration” (humiliating death on the Cross)? But if this is the case, whose power does this display of castration sustain?

I am thinking differently about this. the castration thing, which I see as party with

impotence thing. as a source of power thing.

I used to see the nill fill as a fold in a nitwork of impotence.

but — that has changed — rearranged, into it being about control, and my maintaining control, while writing across time, as something, that is beyond me

and behind me,

and same time liable to be sullen and dreadful they are the char and its burning coal

occurs everyday in the writing. everyday I am leaning out the window by my feet, hanging on to the drapes,

in translations of allegory which I can now hink of —

as wind blown time sheers.

which btw use book on schillling (sp) by you — re discovery of word = change time element, to having a history, or creating a history, and gods as its dimension of sorts. and allegory -- its sensitivity to poetry as a presence in the language

seeing across time into allegorical, as sympathetic with the real

is diff than being in time,

tribs cribs libs … bibs… the sea tin

Europe has been Fascist since the Roman Empire. Fascism and White Supremacism are the milk on which Europeans - and their offspring in the colonies - are reared. Liberalism is a form of Fascism - and you see how ready Liberals are to bomb brown-skinned people to impose their Liberalism on them. Let's not forget that it was slave-trafficking Fascists like John Locke who turned racism into a science. You see how many of our white Liberals are supporting Apartheid and Genocide in Palestine - just as they supported Apartheid and Genocide in Africa, the Americas and Australia. It's very difficult for a European to be anything other than a Fascist. It takes a lot of work - and most Europeans are not willing or able to do that work.