WHEN GOD CRIES: HAMLET AND THE ART OF WORLD-SHATTERING CHANGE

Something Rotten in Denmark

Welcome to the desert of the real!

If you desire the comfort of neat conclusions, you are lost in this space. Here, we indulge in the unsettling, the excessive, the paradoxes that define our existence.

So, if you have the means and value writing that both enriches and disturbs, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

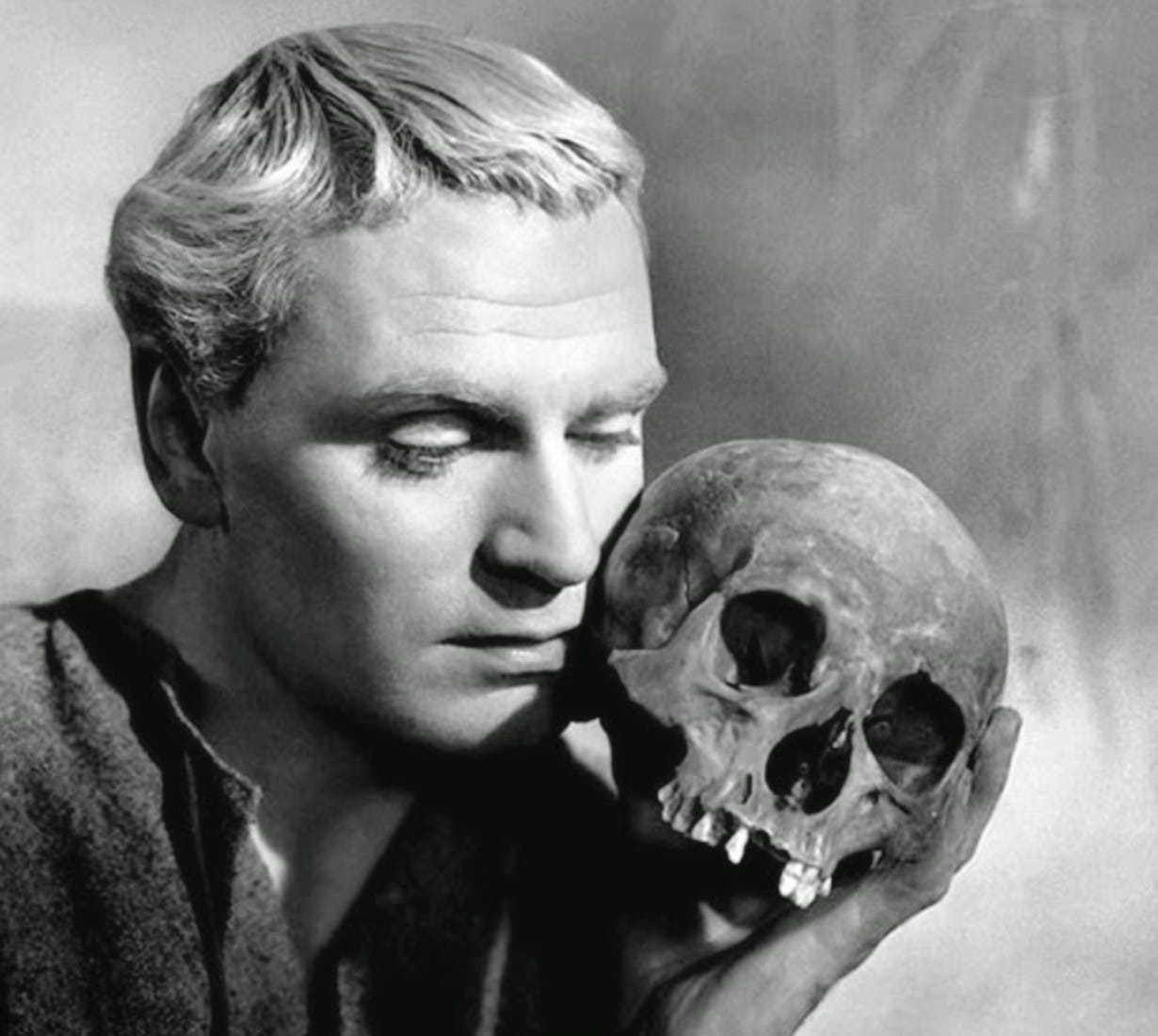

(Picture The Hamlet Project: Laurence Olivier (1948))

When, in his famous essay on Hamlet, T.S. Eliot dismissed it as a failed play much inferior to Romeo and Juliet, lacking basic consistency, he was right for the wrong reason (to paraphrase his own famous line from Murder in the Cathedral): true, Hamlet is inconsistent, lacking basic dramatic unity, but its true achievement resides in this inconsistency itself[1]. It is this very inconsistency which compels almost all philosophers to write something – a brief comment, at least – on Hamlet.

Eliot correctly notes that in the earlier versions of the Hamlet myth, Hamlet uses his perceived madness as a guise to escape suspicion, while in Shakespeare's version, his madness is meant to arouse the king's suspicion rather than avoid it[1]. However, what out-of-joint state does Hamlet react to? What does a true out-of-joint state amount to, at whichever level it takes place? The shortest formal definition is: it doesn't merely change local events within a situation; it changes the coordinates of the situation itself.

Let me paraphrase here an old joke from the GDR: Putin, Xi, and Trump meet God, and each is allowed to ask him a question. Putin begins: "Tell me what will happen to Russia in the next decades?" God answers: "Russia will gradually become a colony of China." Putin turns around and starts to cry. Xi asks the same question: "And what will happen to China in the next decades?" God answers: "The Chinese economic miracle will be over; it will have to return to a hard-line dictatorship to survive while asking Taiwan for help." Xi turns around and starts to cry. Finally, Trump asks: "And what will be the fate of the US after I take over again?" God turns around and starts to cry... This is true change, when God himself (who stands here for the big Other, the neutral frame that encompasses the situation) breaks down.

In this case, it is, of course, a catastrophic change: our basic coordinates for measuring the quality of public life are suspended and will have to be rethought. So, back to Hamlet, what is the catastrophic change that sets the plot in motion? The first reply is that it is not Claudius's murder of the old Hamlet that throws time out of joint; it is the mother's formless desire that does it.

"Hamlet's mother's desire is something that threatens the world as such. It is excessive (it defies the natural order; she has an impossible desire) – but the true libidinal stakes of Hamlet are shown in that her desire is claustrophobic for him; it 'stains' the world as such and makes the world a ruin. It is not simply that Hamlet's mother has a desire that is a problem for Hamlet, but the world outside is indifferent. It is precisely an indication of Hamlet's 'private world' (still under the sway of mother's desire) that the rest of the world can only seem tainted by the private (if my mother has an obscene desire, the world as such must be out of joint)."

A more attentive reading makes it clear that we should go even a step further – as Lacan pointed out, the central enigma of the play is the figure of Ophelia. But we will not follow this path here and rather begin with a popular pseudo-scientific myth about Hamlet, that of the "Hamlet's mill." The central claim of Hamlet's Mill, while problematic with regard to facts, turns around the usual relationship between myths and science: first, there are myths, and through the progress of human knowledge, they are gradually replaced by scientific knowledge. Hamlet's Mill, on the contrary, postulates an original scientific insight (precession) which was then translated into multiple mythic narratives about complications in a royal lineage.

At the core, ancient myths serve as cosmic allegories, reflecting humanity's attempts to comprehend and chart the movements of celestial bodies. Different cultures, from the Inuit of the Arctic to the Egyptians along the Nile, embedded their understanding of the heavens within their mythological frameworks. These myths encapsulated critical astronomical phenomena, chiefly the precession of the equinoxes—a slow, gradual shift in the orientation of Earth's rotational axis, which significantly influences global climate and the timing of seasons over millennia. The precession of the equinoxes holds paramount significance in ancient cosmology, as its recognition indicates a highly advanced level of observational astronomy.

The ancient scholars knew that the stars do not remain fixed in the sky but shift their positions over extended periods. This knowledge was meticulously chronicled and preserved through myth. For instance, the Great Year, a concept famously associated with Plato, is a reflection of this precessional cycle, illustrating an ancient awareness of astronomical cycles spanning approximately 25,920 years, a period during which the Earth's axis completes a full rotation. In this way, myths from various cultures can be seen as different layers and facets of a unified astronomical science, each story illuminating aspects of celestial phenomena and their impact on human life. Thus, ancient myths are not only cultural artifacts but also sophisticated vessels carrying astronomical knowledge across generations. The true enigma is not if there is a deep cosmic scientific insight beneath the myths but exactly the opposite: why does this scientific insight about planets assume in its mythic appearance a very precise familial form: after a king is killed by his brother, who then marries the queen, the king's son fakes madness to gain time for revenge... As Freud repeatedly pointed out, the true secret of a dream (the unconscious desire staged in it) does not reside in the dream's thought but in the form this thought assumes.

As Lacan pointed out, Oedipus doesn't have the Oedipus complex, but Hamlet does have it fully - witness his long confrontation with his mother in the middle of the play. Both stories, Oedipus's and Hamlet's, are universal myths found from Africa and Polynesia to Nordic countries, but in Sophocles and Shakespeare, they get a different spin. In Sophocles's version, Oedipus answers the Sphinx's riddle and thereby pushes it to destroy itself – a unique "philosophical" turn of the myth. (Moreover, Oedipus's answer is strictly wrong in the sense of false philosophical universality which obfuscates the singularity of truth: the correct answer is not "man" (in general) but Oedipus himself who, as a young child, crawled on all fours because he was crippled and who, as an old blind man, had to lean on Antigone to be able to walk.)

Hamlet's myth is also universal – as we have just seen, there are even interpretations which indicate that it originally referred to precession in the circular movement of planets, i.e., to a glitch, an imbalance, in the circular movement of our cosmos itself. But in premodern versions, Hamlet's revenge simply re-establishes the harmony disturbed by the uncle's murder of the father: like in The Lion King, the son kills the uncle and takes over the throne, and time is thereby no longer out of joint but set straight again - we are firmly in the circular movement of a disturbance and its correction. In Shakespeare, however, the deadlock remains; there is no return to the lost balance. In a way that is homologous to Oedipus's wrong answer to the riddle of the Sphinx, Hamlet doesn't see that he himself is ultimately the element "out of joint" in his world, so it is quite logical that at the end, order is restored only when the dying Hamlet proclaims the new king.

Perhaps one could even risk the hypothesis that the bitter split between the two main sects within Islam, Sunni and Shia, echoes the Hamlet's mill topic. The divide originated with a dispute over who should succeed the Prophet Muhammad as leader of the Islamic faith he introduced. After Muhammad's death in A.D. 632, most of Muhammad's followers thought that the elite members of the Islamic community should choose his successor, while a smaller group believed only someone from Muhammad's family—namely his cousin and son-in-law, Ali—should succeed him. This group became known as the followers of Ali; in Arabic, the Shiat Ali, or simply Shia. Eventually, the Sunni majority (named for sunna, or tradition) won out and chose Muhammad's close friend Abu Bakr to become the first caliph, or leader, of the Islamic community. Ali eventually became the fourth caliph (or Imam, as Shiites call their leaders), but only after the two that preceded him had both been assassinated. After Ali himself was assassinated, in 681 his son Hussein led a group of 72 followers and family members from Mecca to Karbala (present-day Iraq) to confront the corrupt caliph Yazid of the Umayyad dynasty. A massive Sunni army waited for them, and by the end of 10 days of skirmishes, Hussein was killed and decapitated, and his head brought to Damascus as a tribute to the Sunni caliph – an act intended by the Umayyads to put the definitive end to all claims to leadership of the ummah as a matter of direct descendance from Muhammad. But it's not what happened: Hussein's martyrdom at Karbala became the central story of Shia tradition – the crime which threw the Muslim community out of joint. Shia enacted the original act which put the Muslim community out of joint, and a similar situation (an Imam being violently deposed and killed) repeats itself a couple of times in later Shia history. From today's perspective, the paradox is that although Shia are more royalist (the bloodline decides who the next leader will be), their politics is, as a rule, much more populist-revolutionary.

However, in interpreting Hamlet, we are not caught between the two extremes: the familial one (Denmark was thrown out of joint with Claudius killing the old Hamlet) and the cosmic one (the ultimate reference of the "out of joint" is the precession in the movement of planets around the Sun). There are clear hints in Hamlet that, even at the familial level, things went wrong and were thrown out of joint already before Claudius killed Hamlet's father: the true source of evil in the play, the one on account of whose acts there is something rotten in Denmark, is the allegedly good old king, Hamlet's father, who defeated Fortinbras in a big battle and liberated Denmark from Norway to whom it was subordinated. Towards the end of the play, we are informed that this took place on the very day of Hamlet's birth. The day of Hamlet's death, we are told by the grave-diggers, is also the 30th anniversary of his birth. On this day, by the nomination of the dying Hamlet, these lands return to the young Fortinbras, "the restorer of order," as Lacan puts it, together with the Kingship of Denmark:

"Mortally wounded, Hamlet assumes his independent political authority for the first time, giving Fortinbras his 'dying voice' as next king. In so doing, Hamlet endorses the figure of his own disavowed potential; Fortinbras represents the obverse of Hamlet's choice, renouncing revenge in exchange for life and the continuation of the family dynasty. Hamlet's dying vote also serves to end Hamlet's own dynastic line, moving the crown outside his extinguished bloodline.

Here are Hamlet's last words: 'I do prophesy the election lights on Fortinbras. He has my dying voice. So tell him, with the occurrents, more and less, which have solicited. The rest is silence. O, O, O, O.' (dies)

'The time is out of joint. O cursed spite, that ever I was born to set it right!' – Hamlet does set it right, but not directly by killing Claudius and becoming king. Things are set straight with Fortinbras taking over. Hamlet's 'I was born to set it right' is to be taken literally: we learn that Hamlet was born 30 years ago, exactly on the day when his father won the battle against the Norwegians and thus perturbed the legitimate order of royal succession[2]. The dying Hamlet sets it right by proclaiming Fortinbras the new legitimate king[4]. Hamlet sets things straight by obliterating his entire bloodline. The only alternative reading is that when Hamlet gives his voice to Fortinbras as a new king, he acts like a traitor to his country, collaborating with a foreign conqueror.

There are thus good arguments for the premise of John Updike's 'Gertrude and Claudius' that Hamlet's father is the truly evil person in the play, and that his injunction to Hamlet is an obscenity. Updike's novel is a prequel to Shakespeare's play: Gertrude and Claudius are engaged in an adulterous affair (Shakespeare is ambiguous on this point), and this affair is presented as passionate true love. Gertrude is a sensual, somewhat neglected wife, Claudius a rather dashing fellow, and old Hamlet an unpleasant combination of brutal Viking raider and coldly ambitious politician. Claudius has to kill the old Hamlet because he learns that the old king plans to kill them both (and he does it without Gertrude's knowledge or encouragement). Claudius turns out to be a good, generous king; he lives and reigns happily with Gertrude, and everything runs smoothly until Hamlet returns from Wittenberg and throws everything out of joint. Whatever we imagine as the (fictional) reality of Hamlet, Gertrude is the only kindhearted and basically honest person in the play.

This brings us to Eliot's basic argument against Hamlet, which is based on his concept of the objective correlative: for him, the greatest contributor to the play's failure is Shakespeare's inability to express Hamlet's emotion in his surroundings and the audience's resultant inability to localize that emotion. The madness of Shakespeare's character, according to Eliot, is a result of the inexpressible things that Hamlet feels and the playwright cannot convey. Because Shakespeare cannot find a sufficient objective correlative for his hero, the audience is left without a means to understand an experience that Shakespeare himself does not seem to understand.

Here's the corrected version with fixes for spelling, grammar, and punctuation:

While in principle agreeing with this description, one should return here to none other than Hegel, to his notion of the end of art with the rise of modern subjectivity. What Eliot designates as the lack of objective correlative perfectly fits Hegel's idea that, in contrast to Ancient art in which the spirit and its bodily representation are in harmony, with modernity the subject turns into something that exceeds every sensual representation. In other words, what Eliot deplores as Shakespeare's failure is the very fact (demonstrated by Cutrofello) that Hamlet is the first great figure of modern subjectivity, a subjectivity defined by the gap that separates it from external reality. In contrast to Harold Bloom's designation of Shakespeare as the inventor of the human, Todd McGowan ironically pointed out that, in Hamlet, Shakespeare rather invented the inhuman core of subjectivity, something that cannot be constrained by the space of interacting humans.

That's why Hamlet's "to be or not to be" has to be read differently, not as a simple alternative. In a quite Hegelian way, Lacan pointed out that we should imagine someone saying "to be or not...", making us expect some determination to follow, a determination which in this case would stand for a symbolic identity that the subject is interpellated into ("... a lover, a man, a woman, a hero"); however, since the subject (Hamlet) is not able to find a symbolic identity that would constitute him as an agent, he stumbles and simply returns to the beginning: "to be or not... to be." So for Lacan, the cut is not between "to be" / "not to be" but between "to be or not" and the second "to be" – the second "to be" is not the same as the first one since it includes negation, negativity that forms the core of a subject.

Such an inhuman subject by definition cannot sing, which is why there cannot be Hamlet as an opera. This cannot be, although there are a dozen or so operas based on Hamlet. Apart from the last one by Brett Dean (a moderate success which premiered at New York Met in 2017), one should mention the big hit, the Ambroise Thomas version from 1868 (based on the French translation by Dumas the elder!) at the end of which Hamlet lives and is proclaimed king. (This is not an innovative attempt by the opera's librettists to rewrite Shakespeare, but a reflection of a highly popular version of Hamlet that was all the rage with nineteenth-century Parisian audiences.) In the final scene, as Gertrude, Claudius, and Laertes are dying, the ghost of Hamlet's father reappears and condemns each of the dying characters. To Claudius it says: "Désespère et meurs!" – "Despair and die!"; to Laertes: "Prie et meurs!" – "Pray and die!"; and to the Queen: "Espère et meure!" – "Hope and die!" When, at the very end of Thomas's version, the wounded Hamlet asks: "Et quel châtiment m'attend donc?" – "And what punishment awaits me?", the ghost responds: "Tu vivras!" – "You shall live!", and the curtain falls... Before we break out in laughter, we should admit that this ending is quite logical. As expected, Ophelia's madness scene is the most popular part of Thomas's version, but it is done more in the style of Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor where Lucia descends into madness, and on her wedding night, while the festivities are still being held in the Great Hall, she stabs her new husband, Arturo, in the bridal chamber. Disheveled, unaware of what she has done, she wanders in the Great Hall, recalling her meetings with Edgardo and imagining herself married to him... there is no complex ambiguity here, just a violent act committed due to a series of misunderstandings which led Lucia to think she was betrayed by her true love.

Such utter artistic failures offer negative proof that Hamlet cannot be made into an opera. Many critics of Cartesian modernity like to insist that we need to bring out what distinguishes a human being from a subject – Hamlet does the exact opposite, he brings out a dimension of subjectivity that cannot be constrained by the space of humanity. And inhuman subjects don't sing.

Citations:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamlet_and_His_Problems

[2] https://xtf.lib.virginia.edu/xtf/view?docId=StudiesInBiblio%2FuvaBook%2Ftei%2Fsibv009.xml

[3] https://literariness.org/2020/07/04/analysis-of-t-s-eliots-hamlet-and-his-problems/

[4] https://targetliterature.com/hamlet-and-his-problems-summary-and-analysis/

[5] https://interestingliterature.com/2017/03/a-short-analysis-of-t-s-eliots-hamlet-and-his-problems/

[6] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69399/hamlet

[7] https://tseliot.com/prose/hamlet

[8] https://hunter220.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/eliot-hamlet-and-his-problems.pdf

Isn't the key thing that is out of joint the move from premodern feudalism (the dead feudal father) and the rise of modernity (the mother's insatiable appetite)? Hamlet is caught between the two worlds and follows Marx by seeing every solid tradition and institution melt. Moreover, Shakespeare also had to move from the old patronage system to being a theater entrepreneur.

I love you Zizek.You are my goat 🐐