THE SUPPER CLUB

Would I have been part of the French Resistance? Not on tonight’s showing. I’d have been on my knees, kissing the jackboot, offering my wife to the Gestapo.

Dear Readers,

Below a contribution from author Hanif Kureishi; a comic, tragic short story. If you want to read more from him, please do so at his Substack here.

A group of friends meet once a month, nine times a year, for supper. This has been going on for twenty-five years, with each member taking turns to host. It is always an enjoyable, drunken affair—good food, wine, and expensive puddings from Soho cake shops.

Working in various branches of the media and entertainment industries, they are familial, their children are friends, and in the summer, they transport these dinners to the south of France, where they live in close proximity for a month.

There are discussions about contemporary politics, the tabloid press, and prostate cancer, as well as work collaborations, fallings-out, and love affairs. They text and phone one another daily, if not hourly. Some friends know politicians, political journalists, and lawyers, so the gossip can be very juicy, often scandalous and cancel-worthy.

One member was, in fact, recently cancelled and forced to retreat to a bunker in Bratislava, where he had less access to the internet and young females. He will be accepted back in due course. These are sardonic and so-called sophisticated people: the cultural elite, not famous but known—although one of them, Chris Hawk, an actor, would be recognised anywhere; a classically trained leading man who made his millions in American romcoms.

Over the years, they’ve mostly agreed with one another. All are socially left-wing—some with radical, Trotskyite histories—and enjoy sneering at the ignorant, racist right, believing themselves to be progressive and civilised.

A core of close friends has remained from the start, each claiming to have begun this monthly supper ritual. But it was Arthur Brisker, a television and film critic with a column in a broadsheet, who started it with a university friend.

It is the end of one such evening, and Arthur is tucking into his banoffee pie when he overhears Chris and Emily, a septuagenarian costume designer, discussing, in their phrasing, the ‘defensive war against terrorists’.

“They’re an ally.”

“And the only democracy in the Middle East.”

Arthur has a prejudice against murder and wars, although he understands how necessary a bit of killing is from time to time, to keep the peace. But the events of the last two years have terrified and repulsed him; a life spent reading about all kinds of man-made horrors had not prepared him for what his phone presents daily—a gateway to unspeakable horrors.

Before hearing this, he was stuffed and stoned, but now, suddenly, is overwhelmed with adrenaline, dismayed that his long-time companions are parroting banal propaganda. He wants to say something; he should, he must. He begins marshalling his arguments, but the conversation has progressed to air fryers.

That night, he struggles to sleep. For hours, he develops his ideas; going over the history of the conflict, the hypocrisies of the media, the vested interests of the British political class and their support of a gangster state. He can hardly bear to contemplate the maniacal sadism at the core of it all, the complicity of the Prime Minister he voted for, the families torn apart by gleeful, pitiless colonisers. And the children… orphaned and hungry. He must stop spiralling.

He checks the time—it's four a.m.—and he envies his wife, sleeping soundly. Is he, he wonders, capable of real thought anymore, or is he just a lazy, well-off London cunt? A boomer who grew up in what he considers to be the most luxurious and privileged period in human history, he recalls the chant, "Hey, hey LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?" A youth spent in the company of radical feminists, Maoists, communists and anti-colonists: what is he now, sharing banoffee pie with a moronic actor whose only skill is to deliver lines written by playwrights, and now neo-Nazis.

What a stupid profession, what a ridiculous little man. But who am I, a mere commentator on these ludicrous people? A life spent in service to the most vacuous game going. I should cancel my Christmas ski trip to Val d’Isère. Why the fuck am I even going to Val d’Isère when people are dying? The missus loves skiing, particularly the après-ski, and she will be annoyed, but I will have to explain that a person should have some principles. Perhaps we will only go for the weekend. I regret not giving Chris both barrels. I will do so at the next supper.

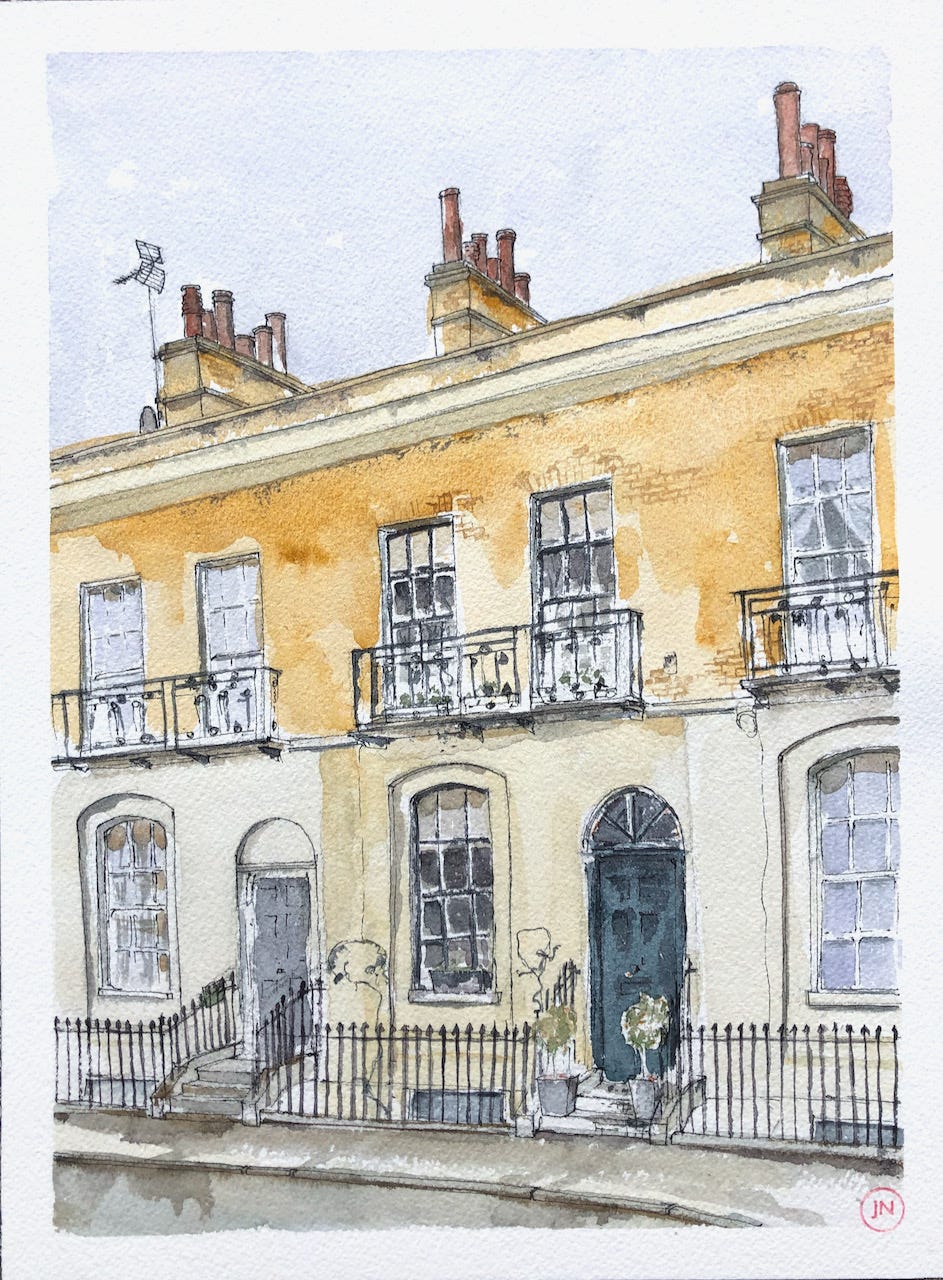

At this month’s do, hosted by the Hawk himself at his luxurious South Kensington, Arthur makes sure he is sitting next to him.

During the last few weeks, and for several hours a day, Arthur has been researching and preparing for an imagined, ferocious debate. On the night of the supper, he drinks less than usual and skips the spliff, ensuring he is as sharp as a boxer before a title fight. The Hawk has recently appeared in a new mini-series and, when not studying, Arthur wrote a positive review of his friend’s performance.

An hour into the meal, the Hawk swivels to Arthur, kisses him on the cheek and neck, and thanks him for the write-up, “I love you man, you know I’ve always loved you. We old white men must stick together.”

Another forty-five minutes pass and Arthur gets drawn into a conversation about a new West End musical with a film director, which they both found abhorrent. Before he knows it, guests are calling Ubers. He has missed his chance for a showdown.

Arthur walks all the way home to Islington in a cold fury. How could I have allowed myself to become so distracted? Where did I lose my focus? I am the embodiment of pathetic complicity. Would I have been part of the French Resistance? Not on tonight’s showing. I’d have been on my knees, kissing the jackboot, offering my wife to the Gestapo.

Another pathetic evening, and yet more sleepless nights of self-flagellation. Arthur makes a commitment. No matter what, at the next supper, he’s going nuclear. He cannot rest in this disgrace. He thinks of the great people of history, those who have spoken out against injustice and fascism, sacrificing everything. Even now, this minute, how many brave martyrs are currently rotting in jails for dissent?

Over his morning coffee, he notices that the current conflict is mentioned on the WhatsApp group. Arthur is shocked to realise that there are more neo-fascist, warmongering collaborators. But he holds his tongue. He will take them on in person.

Meanwhile, he gives money to charities and signs petitions, including one in favour of an organisation the government designates ‘terrorist’. Arthur writes a comment piece in a radical political magazine under a pseudonym, and declines an invitation to a fifteen-course tasting menu at a new high-end Scandinavian restaurant—a gratuitous indulgence he must now do without.

Some nights, Arthur doesn’t go to bed at all. Instead, he drives to Cambridge, where he walks about the deserted city for a few hours, asking himself fundamental, Socratic questions. What is it to be a good person? What is an ethical life? How should one live? He read philosophy here but hasn’t thought about these issues for forty-five years. But why not? Who is he? What is a person who can’t think, who lacks a moral compass, who can’t live in accordance with an ethical ideal?

When he does return to his bed in the early hours, his dreams are so terrible his wife complains that he is shouting and sometimes crying. She decamps to another part of the house, worrying about him.

He arrives early for the next supper. The host, Hughie, a philanthropic ex-banker who has donated generously to the arts, has invited him for a few martinis and a dip in his basement pool.

At his dinners, Hughie employs a familiar crew of chefs and waiters to ensure everyone eats well and their glasses are never empty. When their formerly cancelled friend makes an appearance, looking tanned and greeted with cheers, Arthur becomes worried that the night could be hijacked by stories from the front lines of social and media banishment.

But he will not allow it. He is ready. After an hour, he retreats to the bathroom, splashes cold water on his face and considers his reflection:

“Grandad took down three German bombers. For once, be a man, you jellyfish. There are Nazis out there which you will take on. You must be prepared never to see your friends again.”

He wipes his face with one of the softest towels he’s experienced, making a mental note to find out where it was obtained.

Now, heading towards the dining room, he hears a young female voice he doesn’t recognise:

“…If you are more outraged by the resistance than by the conditions that gave birth to it, then there is nothing else to say—”

Arthur has walked in on quite a scene. The room has turned to look at a waitress, a young black woman with a septum piercing. She stands before them with a bottle of wine in her hand, addressing the Hawk. “Anyway, I’ve said enough. Excuse me for butting in.”

“Please continue,” says the Hawk, “if you’ve got something to contribute, do so, my darling.”

“Well, every system of oppression claims legitimacy,” she goes on, topping up a glass, “Dissent is labelled radical. Never the violence of the state or the status quo.”

“We all want peace, agreed?” says the Hawk, surveying the room. “You’re making it sound like anyone who disagrees is evil.”

“Peace? Please name me a time when liberation was handed over politely, without struggle.”

“My dear,” says the Hawk, “I suggest you educate yourself on the history. They’re an ally, and have a right to defend themselves.”

“My dear,” she repeats, “The right to self-defence is not a blank cheque to rain bombs on a contained, stateless population.”

“Did I say that?”

“Reducing a city to skeletal rubble.”

“It’s a war.”

“Sixty thousand dead,” she says, “according to new reports. Forty percent are children.”

“Excuse me. More wine, please,” interjects a film producer.

As the waitress fills up the glass of a sports writer, he perks up, “You’re only seeing one side."

“Two years of merciless slaughter will do that to you—”

“It’s more complicated than you’re letting on,” he continues.

“The history’s complicated, sure, I don’t contest that. But there’s nothing complicated about genocide.”

“Arthur,” Hughie says, “take your seat, man. What are you doing over there?”

Arthur realises he’s been standing at the edge of the room since he entered, watching the waitress.

At this point, Emily, the costume designer - who Arthur noticed had been fidgeting furiously - pushes her chair back and stands in the way of the waitress as she attempts to pass. Their faces are close.

“You’re a cliché. An angry young woman animated by a war that has nothing to do with her.”

“Our taxes are funding it.”

“You don’t pay any tax.”

“Are you a mother?”

“To three boys.”

“And are you not disgraced by the images of mothers holding the bodies of their dead children, daily?”

“…It’s their children, or ours. Top up, please.”

“Jesus Christ,” the waitress mutters, doing as she’s told, while looking around the room as if inviting a response from the others. She stares directly at Arthur, obliging him to speak. “Emily, you can’t say that.”

“These people,” interrupts a bass player, “whose parents and grandparents were killed in genocides, are committing one themselves now.”

“Please,” says Emily, still standing in the path of the waitress. “There isn’t a genocide. What in hell are you reading?”

“The UN for one. Amnesty. Many others.”

“That’s enough for me,” says a TV producer, throwing down his napkin, readying to leave.

“Now, now,” says Hughie. “Let’s not spoil the evening. We’ve always had discussions. But nothing uncivil.”

“Hughie,” Emily says, “I had no idea how many racists our little suppers harboured. Did you?”

The chef and a waiter, on hearing the din, have charged in. Hughie, who enjoys a ruck, indicates that they should keep back.

The waitress rolls her eyes and says, “You people—” as she attempts again to move past Emily.

“Racist,” Emily says.

“Me?” the waitress laughs, “Look how irate you’ve become. Nothing I’ve said is controversial.”

“Terrorist sympathiser.”

“Excuse me?”

Shaking with fury, Emily looks to her friends for support. “Anyone? She can’t talk to me like that.”

“Come off it,” Arthur says, louder now so the room hears him. “Are you not tired of this exhausted trope? Criticising a maniacal state doesn’t make you a racist.”

“Arthur, you’re a two-bit television critic. My grandparents survived the worst atrocity of the twentieth century.”

“And you find wigs for actresses,” Arthur says. “This brutal country you support is a machine for creating racism against our own people.”

“And would your grandparents,” the waitress says, slamming the bottle down on the table, “not be horrified by what their country is now doing?”

“Shut your mouth!” says Emily.

“Why don’t you shut your mouth and get out of my way so I can do my job?”

Hughie gives the chef a nod. He crosses the room with the waiter and each takes one of the waitress’s arms.

“Come on,” says the chef, “You’re out of here.”

“Gladly.”

“Sorry about this, boss,” the chef says, addressing Hughie. “She won’t be working with us again.”

As she is being taken out, the waitress turns to the room, “You want silence? That’s easy for you. History won’t remember your pathetic debates or your ‘well-meaning’ neutrality. It keeps score of what you are. Privilege has made you cowards.”

She’s right. Of course she’s right. We may be doomed, but at least she exists. If we have a future, she’s it.

“She’s wonderful,” says Hughie, “bit spiky and adolescent. Where did you find her?”

“Fuck you, Chris,” says Arthur, “And fuck all you cunts. Thank God for her.” He picks up a plate and smashes it on the floor.

“Pudding, Arthur?”

But Arthur has gone, running down the front steps and into the street. In the distance, he sees the waitress walking away and he follows her, shouting as he goes, “Miss, miss.”

But she doesn’t hear him.

A contribution from Hanif Kureishi. If you want to read more from him, please do so at his Substack here.

It's a fascinating string of cliches that creates, from my perspective, an unavoidable sense of deja vu. I suppose that's the point, but doesn't the parody risk supplanting or erasing what's supposed to be the bigger, more honest point, namely that Israel is a mafia state on steroids? Also its parodic style is so deja vu-ish it risks being confused with AI generated text.

Thank you for sharing this, Zizek. It's a fantastic piece. Bravo Kureishi!