Comrades,

Welcome to the desert of the real.

Free from all forms of censorship that pervade our media, Žižek goads and prods philosophy, politics, culture, and so on.

For the time being, my writing on here will be entirely free. If you have the means, and believe in paying for good writing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Below is an essay I wrote on my enduring love for Patrica Highsmith, with a note on Andrew Wilson’s BEAUTIFUL SHADOW. A LIFE OF PATRICIA HIGHSMITH, London: Bloomsbury 2003

Let me begin with a personal note: the name “Patricia Highsmith” designates for me a sacred territory, the One whose position among writers is comparable to the place Spinoza holds for Deleuze (the “Christ among philosophers”) – when one talks about Highsmith, one should be careful, since one walks on my dreams. Reading Wilson’s biography was therefore for me a must.

The result? One certainly learns a lot, and the book strikes the right balance between empathy and critical distance, so it IS a must for all those interested in Highsmith and, more generally, in crime fiction. What I find problematic is the level of interpretive reflections, where Wilson often gets dangerously close to banality – can one really take seriously passages like “Highsmith’s fiction, like Bacon’s painting, allows us to glimpse the dark, terrible forces that shape our lives, while at the same time, documenting the banality of evil”(5[1])? Not to mention fast pop-psychology references to Erich Fromm and David Riesman, plus the listing of all existentialist usual suspects from Kierkegaard and Dostoyevsky onwards… Much more pertinent are occasional remarks quoted by Wilson, like Duncan Fallowell’s perspicuous characterization of Highsmith’s personality as “a combination of painful vulnerability and iron will”(423). Or anecdotes which illustrate how Highsmith totally lacked any Politically Correct tact and openly articulated her fantasies and prejudices (although a Leftist, she preferred Margaret Thatcher to the usual feminist bunch). Or the data which indicate the ethico-political grounds of Highsmith’s choice of what some today call the “old Europe”: she “made a life’s work of her ostracization from the American mainstream and her own subsequent self-reinvention”(Frank Rich, quoted in 317) - already in 1954, she described the US as a “second Roman Empire.”

To be sure, the book provides a lot of stuff of what Freud called “wild analysis.” Five months before Highsmith’s birth, her mother tried to rid herself of her unborn child by drinking turpentine; this accident was told to Pat later by her mother herself who voiced her surprise: “It’s funny you adore the smell of turpentine, Pat.”(21) Does this love for, as it were, the mark of her own death or, rather, non-existence, not display the Oedipal wish not to exist, not to be born in the first place? However, such insight pale into insignificance when compared with the wealth of Highsmith’s fictional universe: her work is simply so much more compelling than any secret unearthed by the pseudo-Freudian search for a key to Highsmith‘s morbid universe in her real life experiences. The greatest challenge of the Freudian reading of Highsmith lies elsewhere: to deploy how writing was for her literally what Lacan would have called her sinthome, the “knot“ that held her universe together, the artificial symbolic formation through which she maintained a minimum of sanity by conferring on her tumultuous experience a narrative consistency. In her masterpiece Those Who Walk Away, the hero’s wife justifies her suicide by quoting (what later become) the James Bond phrase: “The world is not enough.” Her writing was for Highsmith that which enabled her to avoid suicide, to endure in a world which, in itself, is not enough.

One often hears that, in order to understand a work of art, one needs to know its historical context. Against this historicist commonplace, the lesson of Highsmith is not only that too much of a historical context can blur the proper contact with a work of art (i.e., that, in order to enact this contact, one should abstract from the work's context). Even more, it is, rather, the work of art itself which provides a context enabling us to properly understand a given historical situation. If, today, someone were to visit Serbia, the direct contact with raw data there would leave him confused. If, however, he were to read a couple of literary works and see a couple of representative movies, they would definitely provide the context that would enable him to locate the raw data of his experience. And the same goes for Highsmith: the task is not so much to explain her work through references to her “real“ life, but, rather, to explain through the reference to her work how she was able to survive in her “real“ life.

So which is Highsmith’s masterpiece? Already her first texts (the short story The Heroine, the novel Strangers on a Train), display an uncanny perfection – everything is already there, no further “growth” was needed, so that there is effectively a Buddha-like quality about Highsmith (according to the legend, Buddha was born as a wise man with silver hair). The interesting fact here is that Highsmith’s only conspicuous artistic failure is her “direct” lesbian novel first published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan as The Price of Salt in 1952, then reprinted under Highsmith’s own name as Carol in 1991. The cause of this failure is, paradoxically, that Carol was too close to Highsmith’s “real life” traumas and concerns: as long as she was compelled to articulate these concerns in an oblique, ciphered way, the result was outstanding; the moment she addressed them directly, "calling them by their name," we got a rather flat and uninteresting novel – is this not the ultimate confirmation of Lacan’s thesis that truth articulates itself in the very distortions and displacements of the central topic?

Among non-Ripley novels, my personal favorite is Those Who Walk Away, which displays Highsmith achievement at its best: she took crime fiction, the most “narrative” genre of them all, and imbued it with the inertia of the real, the lack of resolution, the dragging-on of the “empty time,” which characterize the stupid factuality of life. In Rome, Ed Coleman tries to murder Ray Garrett, a failed painter and gallery-owner in his late 20s, his son-in-law whom he blames for the recent suicide of his only child, Peggy, Ray’s wife. Rather than flee, Ray follows Ed to Venice, where Ed is wintering with Inez, his girlfriend. What follows is Highsmith’s paradigmatic agony of the symbiotic relationship of two men who are inextricably linked to each other in their very hatred. Ray himself is haunted by a sense of guilt for his wife’s death, so he exposes himself to Ed’s violent intentions. Echoing his death wish, he accepts a lift from Ed in a motor-boat; in the middle of the lagoon, Ed pushes Ray overboard. Ray pretends he is actually dead and assumes a false name and another identity, thus experiencing both exhilarating freedom and overwhelming emptiness. He roams like a living dead through the cold streets of wintry Venice when… We have here a crime novel with no murder, just failed attempts at it: there is no clear resolution at the novel’s end – except, perhaps, the resigned acceptance of both Ray and Ed that they are condemned to haunt each other to the end.

Highsmith practiced the literary equivalent of what Deleuze later defined as the shift from “movement-image” to “time-image” in the history of cinema: true art is not simply the telling of stories, but the telling of how stories go wrong, rendering visible and palpable the interstices in which “nothing happens.” In art, spiritual and material are directly intertwined: the spiritual emerges when we become aware of the material inertia, dysfunctional bare presence, of objects around us. The spiritual emerges after a murder attempt goes wrong and the prospective murderer and his victim are left stupidly staring at each other. Highsmith is thus quite literally, more than any author, the writer who elevated crime fiction to the level of art.

This sensibility for the inertia has a special significance for our age in which the obverse of the incessant capitalist drive to produce new objects are the growing piles of useless waste, piled mountains of used cars, computers, etc., like the famous airplane "resting place" in the Mojave desert… in these ever-growing piles of inert, dysfunctional “stuff,” which cannot but strike us with their useless, inert presence, one can, as it were, perceive the capitalist drive at rest. Therein resides the interest of Andrei Tarkovsky's masterpiece Stalker, of its post-industrial wasteland with wild vegetation growing over abandoned factories, concrete tunnels and railroads full of stale water and wild overgrowth in which stray cats and dogs wander. Nature and industrial civilization are here again overlapping, but through a common decay - civilization in decay is in the process of again being reclaimed (not by idealized harmonious Nature, but) by nature in decomposition. The ultimate irony of history is that an author from the Communist East displayed the greatest sensitivity for this obverse of the drive to produce and consume. Perhaps, however, this irony displays a deeper necessity which hinges on what Heiner Mueller called the "waiting-room mentality" of the Communist Eastern Europe:

"There would be an announcement: The train will arrive at 18.15 and depart at 18.20 -- and it never did arrive at 18.15. Then came the next announcement: The train will arrive at 20.10. And so on. You went on sitting there in the waiting room, thinking: It's bound to come at 20.15. That was the situation. Basically, a state of Messianic anticipation. There are constant announcements of the Messiah's impending arrival, and you know perfectly well that he won't be coming. And yet somehow, it's good to hear him announced all over again."

The point of this Messianic attitude was not that hope was maintained, but that, since the Messiah did NOT arrive, people started to look around and take note of the inert materiality of their surroundings, in contrast to the West where people, engaged in permanent frantic activity, do not even properly notice what goes on around them: because of the lack of acceleration, people enjoyed more contact with the earth on which the waiting room was built; caught in this delay, they deeply experienced the idiosyncrasies of their world, all its topographical and historical details… One can easily imagine a Highsmith hero, Ray or Ed, stuck at such an East German railway station - Highsmith induced us to look at our own environs through the East German eyes.

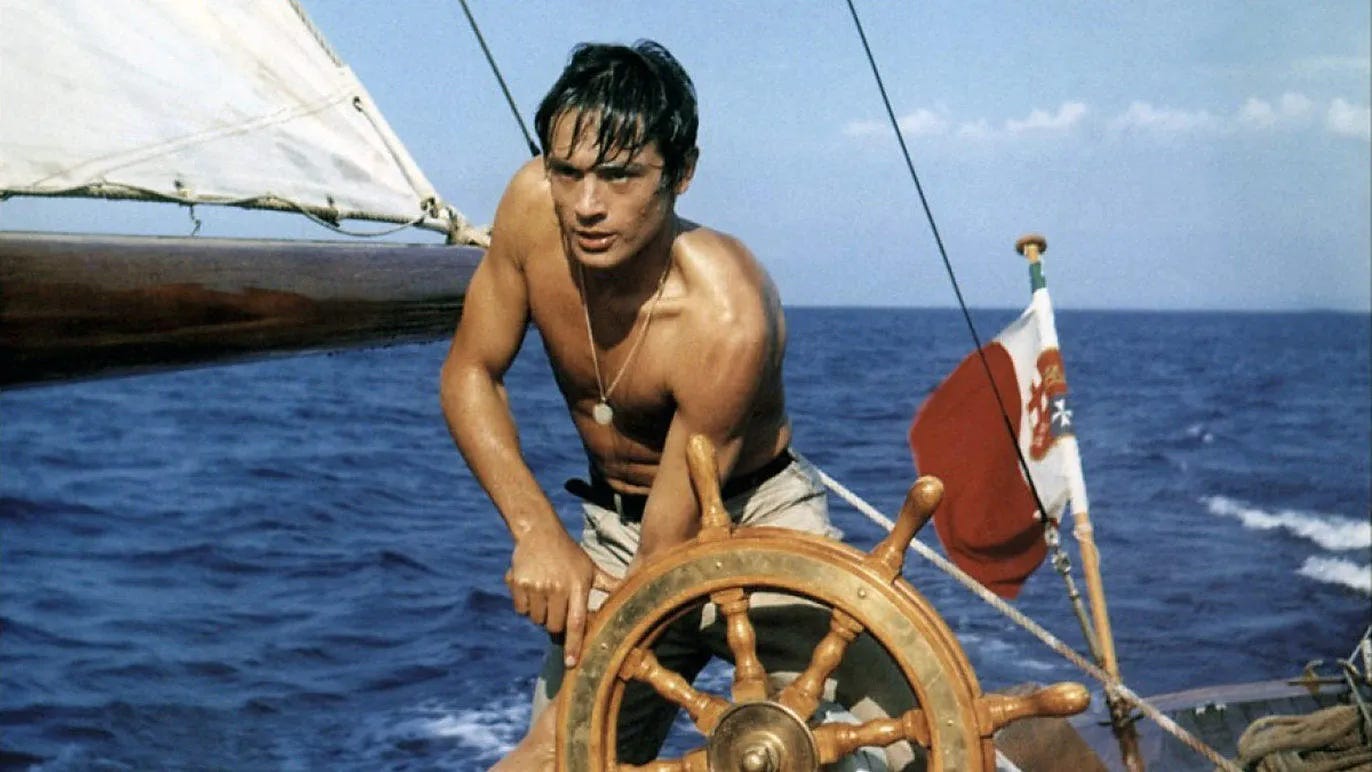

However, such an environs of material decay and failed decisions is only half of the story: is a HERO proper still imaginable, who would walk along these decrepit streets and counteract their inertia? Highsmith reply is Tom Ripley, the hero of her five novels. Ripley is difficult to swallow, and the best indicator of this difficulty is the failure of his four cinema versions. First, there were Alain Delon in Rene Clement’s Plein Soleil (1960, based on The Talented Mr Ripley – but in the film, the police at the end arrests Ripley, to Highsmith’ dismay), and Denis Hopper in Wim Wenders’ The American Friend (1977, based on Ripley’s Game); then, in strangely symmetrical remakes, there were Matt Damon in Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr Ripley (1999) and John Malkovich in a new Ripley’s Game by Liliana Cavani (2003). Although, in themselves, all four are outstanding movies, their Ripley is simply not the Highsmith Ripley, they somehow humanize Ripley’s inhuman core: Delon is a cold blooded demoniac European; Hopper is a Sam Shepard type existentialist cowboy; Damon is a hystericized, emotionally unstable, American brat; and Malkovich displays his standard decadent ironic coldness.

Who, then, is the “real” Ripley? Let us take Minghella’s film, where the contrast is most perspicuous. Tom Ripley, a broke young New Yorker, is approached by the rich magnate Herbert Greenleaf, in his mistaken belief that Tom has been at Princeton with his son Dickie. Dickie is off idling in Italy, and Greenleaf pays Tom to go to Italy and bring his son back and to his sense, to take the rightful place in the family business. However, once in Europe, Tom gets more and more fascinated not only by Dickie himself, but also by the polished, easy-going, socially acceptable upper-class life that Dickie inhabits. All the talk about Tom's homosexuality is here misplaced: Dickie is for Tom not the object of his desire, but the ideal desiring subject, the subject "supposed to know /how to desire/." In short, Dickie becomes for Tom his ideal ego, the figure of his imaginary identification: when he repeatedly casts a coveting side-glance at Dickie, he does not thereby betray his erotic desire to engage in sexual commerce with him, to HAVE Dickie, but his desire to BE like Dickie. So, to resolve this predicament, Tom concocts an elaborated plan: on a boat trip, he kills Dickie and then, for some time, assumes his identity. Acting as Dickie, he organizes things so that, after Dickie's "official" death, he inherits his wealth; when this is accomplished, the false "Dickie" disappears, leaving behind a suicide note praising Tom, while Tom again reappears, successfully evading the suspicious investigators, even earning the gratitudes of Dickie's parents, and then leaves Italy for Greece.

Although the novel was written in the mid-50s, Highsmith foreshadows today's therapeutic rewriting of the ethical Commandments into "Recommendations" which one should not follow too blindly. Ripley simply stands for the last step in this rewriting: thou shalt not kill - except when there is really no other way to pursue your happiness. Or, as Highsmith herself put it in an interview: "He could be called psychotic, but I would not call him insane because his actions are rational. /.../ I consider him a rather civilized person who kills when he absolutely has to." Ripley is thus not any kind of the "American psycho": his criminal acts are not frenetic passages a l'acte, outbursts of violence in which he releases the energy hindered by the frustrations of the yuppie daily life. His crimes are calculated with simple pragmatic reasoning: he does what is necessary to attain his goal (the wealthy quiet life in the exclusive Paris suburbs). What is so disturbing about him, of course, is that he somehow seems to lack the elementary moral sense: in the daily life, he is mostly friendly and considerate (although with a touch of coldness), and when he commits a murder, he does it with regret, quickly, as painlessly as possible, in the same way one performs an unpleasant but necessary task. Ripley is the best exemplification of what Lacan had in mind when he claimed that normality is the special form of psychosis - of not being traumatically caught in the symbolic cobweb, of retaining the "freedom" from the symbolic order.

The mystery of Highsmith's Ripley transcends the standard American ideological motif of the capacity of the individual to radically "reinvent" him/herself, to erase the traces of the past and assume a thoroughly new identity, it transcends the postmodern "Protean Self". Therein resides the ultimate shift of Minghella’s movie with regard to the novel: the film "gatsbyizes" Ripley into a new version of the American hero who recreates his identity in a murky way. What gets lost here is best exemplified by the crucial difference between the novel and the film: in the film, Ripley has the stirrings of a conscience, while in the novel, the qualms of conscience are simply beyond his grasp. This is why the making-explicit of Ripley's gay desires in the film also misses the point. Minghella implies that, back in the 50s, Highsmith had to be more circumspect to make the hero palatable to the large public, while today we can say things in a more overt way. However, Ripley's coldness is not the surface effect of his gay stance, but rather the other way round. In one of the later Ripley novels, we learn that he makes love once a week to his wife Heloise, as a regular ritual - there is nothing passionate about it, Tom is like Adam in paradise, prior to the Fall, when, according to St Augustine, he and Eve DID have sex, but it was performed as a simple instrumental task, like sowing the seeds on a field. One way to read Ripley is thus to claim that he is angelic, living in a universe which precedes the Law and its transgression (sin), i.e. the vicious superego cycle of guilt generated by our very obedience to the law, described by Paul. This is the reason why Ripley feels no guilt or even remorse after his murders: he is not yet fully integrated into the symbolic law.

The paradox of this non-integration is that the price Ripley pays for it is his inability to experience intense sexual passion - a clear proof of how there is no sexual passion outside the confines of the symbolic law. In one of the later Ripley novels, the hero sees two flies on his kitchen table and, upon looking at them closely and observing that they are copulating, squashes them with disgust. This small detail is crucial - Minghella's Ripley would NEVER have done something like this: Highsmith's Ripley is in a way disconnected from the reality of flesh, disgusted at the real of life, of its cycle of generation and corruption. Marge, Dickie's girlfriend, provides an adequate characterization of Ripley: "All right, he may not be queer. He's just a nothing, which is worse. He isn't normal enough to have any kind of sex life." Insofar as such coldness characterizes a certain radical lesbian stance, one is tempted to claim that, rather than being a closet gay, the paradox of Ripley is that he is a male lesbian. (No wonder that Highsmith as a lesbian felt such proximity to the figure of Ripley.)

Minghella’s Ripley makes it clear what is wrong with the procedure which appears to be "more radical than the original," bringing out its implicit, repressed content: what mattered in Highsmith’s original was not only the "repression" of the allegedly prohibited (sexual, etc.) content, but the void of this repression as such. What is lost in the gesture of filling in the gaps is Ripley’s non-psychological cold monstrosity, uncannily close to a weird "normality." By way of "filling in the void" and "telling it all," Minghella retreats from the void as such, which, of course, is ultimately none other than the void of subjectivity. Instead of a polite person who is at the same time a monstrous automaton with no inner turmoil, we get the “wealth of a personality,” a person full of psychic traumas - in short, we get someone whom we can, in the fullest meaning of the term, understand.

Tom Ripley was not just a mask for Highsmith, he was quite literally her externalized ego: as we learn in Wilson’s book, she even changed her name into Patricia Highsmith-Ripley and signed her mail with “Tom (Pat)”. One cannot but recall here the old Taoist quip on man dreaming he is a butterfly or vice versa: was Highsmith dreaming that she is Ripley or was she Ripley dreaming, in his daily social life, that he is Highsmith the writer? The ultimate core of this fascination is ethical: Ripley provides what is arguably the clearest and most radical rendering of the difference between morality and ethics – he is immoral, and yet thoroughly ethical. Are we able to sustain this position today when all the rules imposed on us do the exact opposite, seducing us with the promise “if only you follow these elementary moral rules, you can be as unethical as you want”?

[1] All quotes from Wilson’s book are designated just by the page number in brackets.

Greetings comrade! Substack is the place to avoid censorship. Great to see another legendary writer join our ranks.

“Who is the ‘real’ Ripley?”

Watching the movie I recalled this quote by Lacan,

“Mimicry reveals something in so far as it is distinct from what might be called an itself that is behind. The effect of mimicry is camouflage.... It is not a question of harmonizing with the background, but against a mottled background, of becoming mottled - exactly like the technique of camouflage practised in human warfare.”