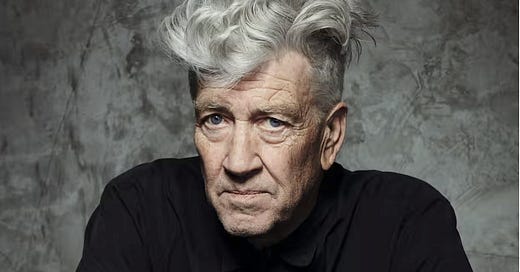

DAVID LYNCH IS DEAD, BUT HIS ETHICS IS MORE ALIVE THAN EVER

Ethics as the most dark and daring of conspiracies

Welcome to the desert of the real!

If you desire the comfort of neat conclusions, you are lost in this space. Here, we indulge in the unsettling, the excessive, the paradoxes that define our existence.

So, if you have the means and value writing that both enriches and disturbs, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

There is something even worse than being swallowed by the reality of a sexual act not sustained by the fantasmatic screen: its exact opposite—the confrontation with the fantasmatic screen deprived of the act. This is precisely what occurs in one of the most painful and troubling scenes from Lynch's Wild at Heart. In a lonely motel room, Willem Dafoe exerts rude and coercive pressure on Laura Dern: he touches and squeezes her, invading her intimate space while repeatedly and threateningly demanding, "Say 'fuck me!'"—attempting to extort from her a word that would signal her consent to a sexual act. The ugly, unpleasant scene drags on, and when Dern, exhausted, finally utters a barely audible "Fuck me," Dafoe abruptly steps away. He assumes a friendly smile and cheerfully retorts, "No, thanks, I don't have time today; but on another occasion, I would do it gladly."

The uneasiness of this scene resides in the fact that Dafoe's unexpected rejection of Dern's forcefully extorted offer delivers the ultimate humiliation. His refusal becomes his triumph, degrading her even more than direct rape might have. He achieves what he truly desires—not the act itself but her consent to it, symbolizing her humiliation. What unfolds here is a form of rape in fantasy that refuses its realization in reality, thereby further degrading its victim. The fantasy is aroused only to be abandoned and thrown back upon the victim. It is evident that Laura Dern's character is not simply disgusted by Dafoe's (Bobby Peru's) brutal intrusion into her intimacy; just before she utters "Fuck me," the camera focuses on her right hand as she slowly spreads her fingers—a sign of acquiescence and proof that he has stirred up her fantasy.

This scene can be interpreted through a Lévi-Straussian lens as an inversion of the standard seduction narrative. In the typical scenario, a gentle approach culminates in a brutal sexual act after the woman finally says "Yes." Here, however, Bobby Peru's polite rejection of Dern's coerced "Yes" has its traumatic impact because it exposes the paradoxical structure of the empty gesture that constitutes the symbolic order. After brutally extracting her consent to the sexual act, Peru treats her "Yes" as an empty gesture to be politely declined—brutally confronting her with her own underlying fantasmatic investment in it.

How can such an ugly, repulsive figure like Bobby Peru stir up Laura Dern's fantasy? Here we touch upon the motif of ugliness itself: Bobby Peru is grotesque and repellent because he embodies the dream of non-castrated phallic vitality in all its raw power. His entire body evokes a gigantic phallus, with his head resembling the head of a penis. Even his final moments reflect this raw energy: after a bank robbery goes wrong, he blows off his own head—not in despair but with merry laughter. Bobby Peru thus belongs to a lineage of larger-than-life figures of self-enjoying evil. A more formulaic but well-known example from Lynch’s work is Frank (Dennis Hopper) in Blue Velvet. One could even argue that Bobby Peru represents the ultimate embodiment of such figures—a culmination of the archetype explored in Orson Welles' films.

"Bobby Peru is physically monstrous, but is he morally monstrous as well? The answer is both yes and no. Yes, because he commits crimes for self-preservation; no, because from a higher moral standpoint, he possesses qualities—at least in certain respects—that elevate him above Sailor (Nicolas Cage), who lacks what might be called Shakespearean vitality. These exceptional beings cannot be judged by ordinary laws; they are both weaker and stronger than others... stronger because they are directly connected to the true nature of things—or perhaps even to God."

This famous description by André Bazin of Quinlan in Welles' Touch of Evil fits Bobby Peru almost perfectly when names are substituted.

Another way to interpret this scene from Wild at Heart is through its underlying reversal of standard gender roles in heterosexual seduction dynamics. Willem Dafoe’s exaggerated features—his oversized mouth with thick wet lips spitting saliva, contorted into obscene expressions with dark twisted teeth—evoke imagery reminiscent of vagina dentata. His grotesque appearance functions as a vulgar provocation—a visual cue likened to a vaginal opening itself inciting Dern’s reluctant “Fuck me.”

This reference to Dafoe's distorted face as a proverbial "cuntface" suggests that beneath the surface narrative—of an aggressive male imposing himself on a female victim—another fantasmatic scenario unfolds. Here, we see a reversal: an innocent young boy (symbolized by Dern) aggressively provoked and then rejected by an overripe, vulgar woman (embodied by Dafoe). At this level of interpretation, traditional sexual roles are inverted: Dafoe becomes the woman teasing and provoking the innocent boy. Again, what is so unsettling about the Bobby Peru figure is its ultimate sexual ambiguity, oscillating between the non-castrated raw phallic power and the threatening vagina—the two facets of the pre-symbolic life-substance. The scene is thus to be read as the reversal of the standard Romantic motif of "death and the maiden": what we have here is "life and the maiden."

This scene with Bobby Peru in Wild at Heart has to be read together with another, no less painful, scene from Lynch’s Blue Velvet, in which Eddy (a gangster master figure) takes Pete (the film’s hero) for a ride in his expensive Mercedes to detect what is wrong with the car. When a guy in an ordinary limo unfairly overtakes them, Eddy pushes him off the road with his stronger Mercedes and then gives him a lesson: with his two thuggish bodyguards, he threatens the stiff-scared ordinary guy with a gun and then lets him go, furiously shouting at him to "learn the fucking rules." It is crucial not to misread this scene, whose shockingly comical character can easily deceive us: one should risk taking Eddy’s figure thoroughly seriously, as someone who is desperately trying to maintain a minimum of order—i.e., to enforce some elementary "fucking rules" in this otherwise crazy universe.

Along these lines, one is even tempted to rehabilitate the ridiculously obscene figure of Frank in Blue Velvet as the obscene enforcer of the Rules. Figures like Eddy (Lost Highway), Frank (Blue Velvet), Bobby Peru (Wild at Heart), or even Baron Harkonnen (Dune) are figures of excessive, exuberant assertion and enjoyment of life—they are somehow evil "beyond good and evil." Yet Eddy and Frank are, at the same time, enforcers of fundamental respect for the socio-symbolic Law. Therein resides their paradox: they are not obeyed as authentic paternal authorities; they are physically hyperactive, hectic, exaggerated, and as such already inherently ridiculous. In Lynch's films, the law is enforced through a ridiculous, hyperactive, life-enjoying agent.

The very beginning of David Lynch's The Straight Story, with the words that introduce the credits—"Walt Disney Presents - A David Lynch Film"—provides what is perhaps the best résumé of the ethical paradox that marked the end of the 20th century: the overlapping of transgression with norm. Walt Disney, the brand of conservative family values, takes under its umbrella David Lynch, an author who epitomizes transgression by bringing to light the obscene underworld of perverted sex and violence that lurks beneath the respectable surface of our lives.

Today, more and more, the cultural-economic apparatus itself—in order to reproduce itself under market competition conditions—has not only to tolerate but directly to incite stronger and stronger shocking effects and products. Suffice it to recall recent trends in visual arts: gone are the days when we had simple statues or framed paintings. What we get now are exhibitions of frames themselves without paintings; exhibitions featuring dead cows and their excrements; videos showing the inside of the human body (gastroscopy and colonoscopy); inclusion of smell into exhibitions; etc. Here again, as in sexuality, perversion is no longer subversive: shocking excesses are part of the system itself—the system feeds on them in order to reproduce itself.

If Lynch's earlier films were also caught in this trap, what then about The Straight Story, based on the true case of Alvin Straight—an old crippled farmer who motored across the American plains on a John Deere lawnmower to visit his ailing brother? Does this slow-paced story of persistence imply renunciation of transgression—a turn toward naive immediacy or a direct ethical stance of fidelity? The very title of the film undoubtedly refers to Lynch's previous opus: this is the straight story with regard to his "deviations" into uncanny underworlds from Eraserhead to Lost Highway. However, what if the "straight" hero of Lynch's last film is effectively much more subversive than the weird characters populating his previous films? What if, in our postmodern world where radical ethical commitment is perceived as ridiculously out-of-time, he is actually the true outcast?

One should recall here G.K. Chesterton's old perspicuous remark in his A Defense of Detective Stories about how detective stories "keep in some sense before the mind the fact that civilization itself is the most sensational of departures and the most romantic of rebellions. When the detective in a police romance stands alone and somewhat fatuously fearless amid the knives and fists of a thieves' kitchen, it does certainly serve to make us remember that it is the agent of social justice who is the original and poetic figure, while burglars and footpads are merely placid old cosmic conservatives happy in their immemorial respectability as apes and wolves. The police romance...is based on the fact that morality is the most dark and daring of conspiracies."

What then if THIS is ultimately Lynch's message—that ethics is "the most dark and daring of all conspiracies," that it is the ethical subject who effectively threatens existing orders? This stands in contrast to Lynch’s long series of weird perverts

(Baron Harkonnen in Dune, Frank in Blue Velvet, Bobby Peru in Wild at Heart...) who ultimately sustain it? Perhaps the opposition between Lynch's "straight" hero and his ridiculously excessive master figures determines the extreme coordinates of today's late capitalist ethical experience—with the strange twist that Bobby Peru is uncannily "normal," while Lynch's "straight" man is uncannily weird, even perverted. Thus, we encounter the unexpected opposition between the weirdness of a thorough ethical stance and the monstrous "normality" of a thoroughly unethical stance.

Recall Brecht's slogan: "What is the robbing of a bank compared to the founding of a new bank?" Therein resides the lesson of David Lynch's The Straight Story: what is the ridiculously pathetic perversity of figures like Bobby Peru in Wild at Heart or Frank in Blue Velvet compared to deciding to traverse the U.S. central plains on a tractor to visit a dying relative? Measured against this act, Frank's and Bobby's outbreaks of rage appear as the impotent theatrics of old and sedate conservatives.

[1] See Michel Chion, David Lynch, London: BFI 1995.

[1] See Andre Bazin, Orson Welles: A Critical View, New York: Harper and Row 1979, p. 74.

[1] G.K. Chesterton, "A Defense of Detective Stories," in H. Haycraft, ed., The Art of the Mystery Story, New York: The Universal Library 1946, p. 6.

Lynch may be the filmmaker of ethics' obscenity par excellence, but we can also trace this idea from Lacan's reading of Antigone through Sethe. In the noir mode of filmmaking, the demands of the ethical almost always occasion defiance of the law (lower case 'l,' as in 'legal') which Lynch took to the most exacting extremes. RIP.

Great article as always. Lynch seemed to have a pulse to the *weirdness* of desire, and the way he used the logic of dreams to convey that ad-infinitum relationship was powerful. He reminds me of a Lacan who thought there *really could be a sexual relationship,* that humanity could get over its "one true failure," that we could all Really love each other beyond the imaginary. I think Twin Peaks did that really well. Powerful as always!