Comrades,

Welcome to the desert of the real.

I’m holding a flash sale;

This week, yearly subscriptions will be priced at just $25.00.

That’s less than three dollars a month for all my writing.

Your subscriptions keep this page going, so if you have the means, and believe in paying for good writing, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

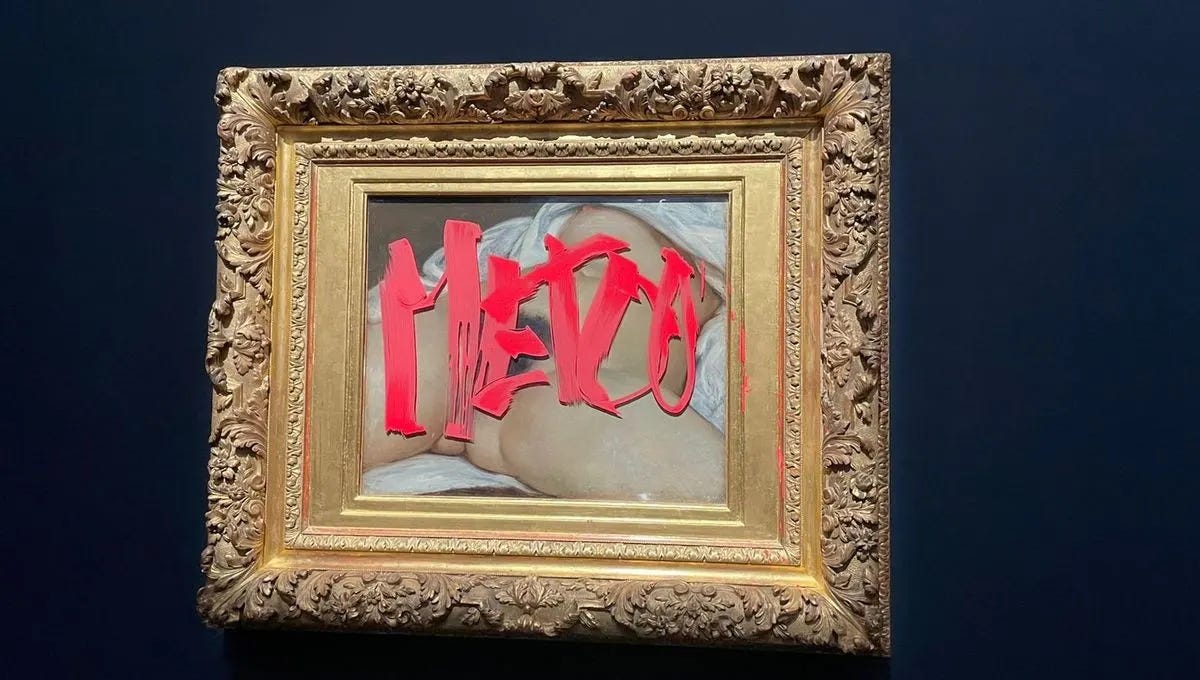

The story is well known: in Metz, an incident occurred at the exposition of art works linked to Jacques Lacan. Two feminists staged a protest in front of Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World owned by Lacan; Deborah de Robertis wrote ‘MeToo’ on the painting which depicts a headless torso of a sexually aroused naked woman’s body, focused on her hairy vulva. The title of a predominant feminist reaction tells it all: “Hurrah for the Courbet vandals: defacing the vulva painting is basic feminism” – de Robertis “is right to think the painting is misogynistic: the model doesn’t even have a face!”[1]

Are things really so clear and simple? While fully respecting the feminist objections as well as rejecting the traditionalist academic disdain for the de Robertis’s act, I think things are more complex. Yes, there is a long history of a woman’s dismembered by a (male) painter. Recall “A Woman Throwing a Stone” (Picasso, 1931): the distorted fragments of a woman on a beach throwing a stone are, of course, a grotesque misrepresentation, if measured by the standard of realist reproduction; however, in their very plastic distortion, they immediately/intuitively render the Idea of a “woman throwing a stone,” the “inner form” of such a figure. Upon a closer look, one can easily discern the steps of the process of (what Husserl would have called) “eidetic reduction” of the woman to her essential features: hand, stone, breasts… this painting thinks, it performs the violent process of tearing apart the elements which, in their natural state, co-exist in reality. However, the problem is WHAT does this painting think – one should not forget that it was made by a male painter tearing apart a woman’s body…

So let’s begin with politics. Courbet was imprisoned for six months in 1871 for his involvement with the Paris Commune and lived in exile in Switzerland from 1873 until his death four years later. As for the fact that the torso is headless, we should remember that back in 2014, de Robertis already performed a feminist act in Musee d’Orsay: in front of the same painting, she sat down with her legs widely spread, fully exposing her vulva to the spectators.[2] This confrontation of the real displayed vagina with her fantasmatic double on a painting produces the effect of "This is not a vagina," like that of "This is not a pipe" in the famous Magritte painting - the scene in which a real person is shown side by side with the ultimate image of what she is in the fantasy for the male Other. But is a woman really more “objectivized” when painted as a headless torso?

To grasp what is happening here, on should recall the paradigmatic hard-core sexual position (and shot) which is easy to identify: the woman is lying on her back with her legs spread wide backwards and with her knees above her shoulder; the camera is in front, showing the man’s penis penetrating her vagina (the man’s face is as a rule invisible, he is reduced to an instrument), but what we see in the background between her thighs is her face in the thrall of orgasmic enjoyment. This minimal “reflexivity” is crucial: if we were just to see the close-up of penetration, the scene would soon turn boring, disgusting even, more of a medical showcase – one has to add the woman’s enthralled gaze, the subjective reaction to what is going on. Furthermore, this gaze is as a rule not addressed at her partner who is doing it but directly at us, viewers, confirming to us her enjoyment – we, spectators, clearly play the role of the big Other who has to register her enjoyment. The pivot of the scene is thus not male (her sexual partner’s or the spectator’s) enjoyment: the spectator is reduced to a pure gaze, the pivot is woman’s enjoyment (staged for the male gaze, of course). The sad irony here is that the very fact that the woman is not “objectivized” but rendered as a subject makes her humiliation worse: she has to fake her enjoyment. Being compelled to enact fake subjective engagement is much worse than being reduced to an object.

So, back to the photo of the painting and the “real” de Robertis displaying her vulva: the paradox is that, no matter what her intentions were, the real de Robertis displaying her vulva is much closer to pornography than Courbet’s painting precisely because her vulva is accompanied by her gaze (her head looking at us), while the effect of Courbet’s painting is much more disturbing – why, precisely? While it is not, of course, a feminist painting in any sense (it clearly addresses a male gaze), it clearly renders the deadlock (or dead end) of the traditional realist painting, whose ultimate object - never fully and directly shown, but always hinted at, present as a kind of underlying point of reference - was the naked and thoroughly sexualized feminine body as the ultimate object of male desire and look. The exposed feminine body functioned here in a way similar to the underlying reference to the sexual act in the classic Hollywood, best described by the famous instruction of the movie tycoon Monroe Stahr to his scriptwriters from Scott Fitzgerald's The Last Tycoon:

"At all times, at all moments when she is on the screen in our sight, she wants to sleep with Ken Willard. ... Whatever she does, it is in place of sleeping with Ken Willard. If she walks down the street she is walking to sleep with Ken Willard, if she eats her food it is to give her enough strentgh to sleep with Ken Willard. But at no time do you give the impression that she would even consider sleeping with Ken Willard unless they were properly sanctified."

The exposed feminine body is thus the impossible object, it functions as the ultimate horizon of representation whose disclosure is forever postponed - in short, it functions as the Lacanian incestuous Thing. Its absence, the Void of the Thing, is then filled in by "sublimated" images of beautiful, but not totally exposed, feminine bodies, i.e. by bodies which always maintain a minimum of distance towards That. But the crucial point (or, rather, the underlying illusion) of the traditional painting is that the "true" incestuous naked body nonetheless waits there to be discovered - in short, the illusion of traditional realism does not reside in the faithful rendering of the depicted objects; it rather resides in the belief that, BEHIND the directly rendered objects, there effectively IS the absolute Thing which could be possessed if we were only able to discard the obstacles or prohibitions that prevent access to it.

What Courbet accomplished in his “Origin” is the gesture of radical desublimation: he made the risky move and simply went to the end by way of directly depicting what the previous realistic art was just hinting at as its withdrawn point of reference - the outcome of this operation, of course, was the reversal of the sublime object into abject, into an abhorring, nauseating excremental piece of slime. (More precisely, Courbet masterfully continued to dwell at the very blurred border that separates the sublime from the excremental: the woman's body in "L'origine" retains its full erotic attraction, yet it becomes repulsive precisely on account of this excessive attraction.) Courbet's gesture is thus a dead end: the dead end of the traditional realist painting - but precisely as such, it is a necessary "mediator" between traditional and modernist art, i.e. it stands for a gesture that had to be accomplished if we are to "clear the ground" for the emergence of the modernist "abstract" art. How?

With Courbet, we learn that there is no Thing behind its sublime appearance, that if we force our way through the sublime appearance to the Thing itself, all we get is a suffocating nausea of the abject - so the only way to reestablish the minimal structure of sublimation is to directly stage THE VOID ITSELF, the Thing as the Void-Place-Frame, without the illusion that this Void is sustained by some hidden incestuous Object. One can now understand in what precise way, and paradoxical as it may sound, Malevitch's "Black Square" as the seminal painting of modernism is the true counterpoint to (or reversal of) "L'origine": in Courbet, we get the incestuous Thing itself which threatens to implode the Clearing, the Void in which (sublime) objects (can) appear, while in Malevitch, we get its exact opposite, the matrix of sublimation at its most elementary, reduced to the bare marking of the distance between foreground and background, between a wholly "abstract" object (square) and the Place that contains it. The "abstraction" of the modernist painting is thus to be conceived as a reaction to the over-presence of the ultimate "concrete" object, the incestuous Thing, that turns it into a disgusting abject, i.e. that turns the sublime into an excremental excess.

So far from being a simple male-chauvinist depiction of the object of desire, Courbet’s “Origine” confronts the male desire with its deadlock: what you really desire is a headless monster, and it is your gaze (sustained by desire) which decapitates the woman.

[1] Hurrah for the Courbet vandals: defacing the vulva painting is basic feminism | Painting | The Guardian.

[2] See Centre Pompidou: Deborah de Robertis en remet une couche à Metz | Bilan.

P.S. So yes, back to the title of this text, I of course know very well that vagina is in French masculine (“le vagin”), but therein resided my ironic point unnoticed by those who thought they caught me in an embarrassing mistake: vagina in (my fake) French (“la vagine”) is a part of the entire feminine body (head, legs and arms included), and “le vagin” is not feminine but part of a headless monstrosity constructed by masculine fantasy. “Ceci n’est pas une vagine” is thus quite literally true: what we see on the painting is le vagin - so it should be "ceci est un vagin."

Thank you for this, but you misgendered vagina in your title which, curiously, is masculine in French: un vagin. Another curiosity, Magritte's original title: Ceci n'est pas une pipe is a double entendre because "une pipe" is French slang for a blow job . Language is a hall of mirrors from which we cannot emerge.