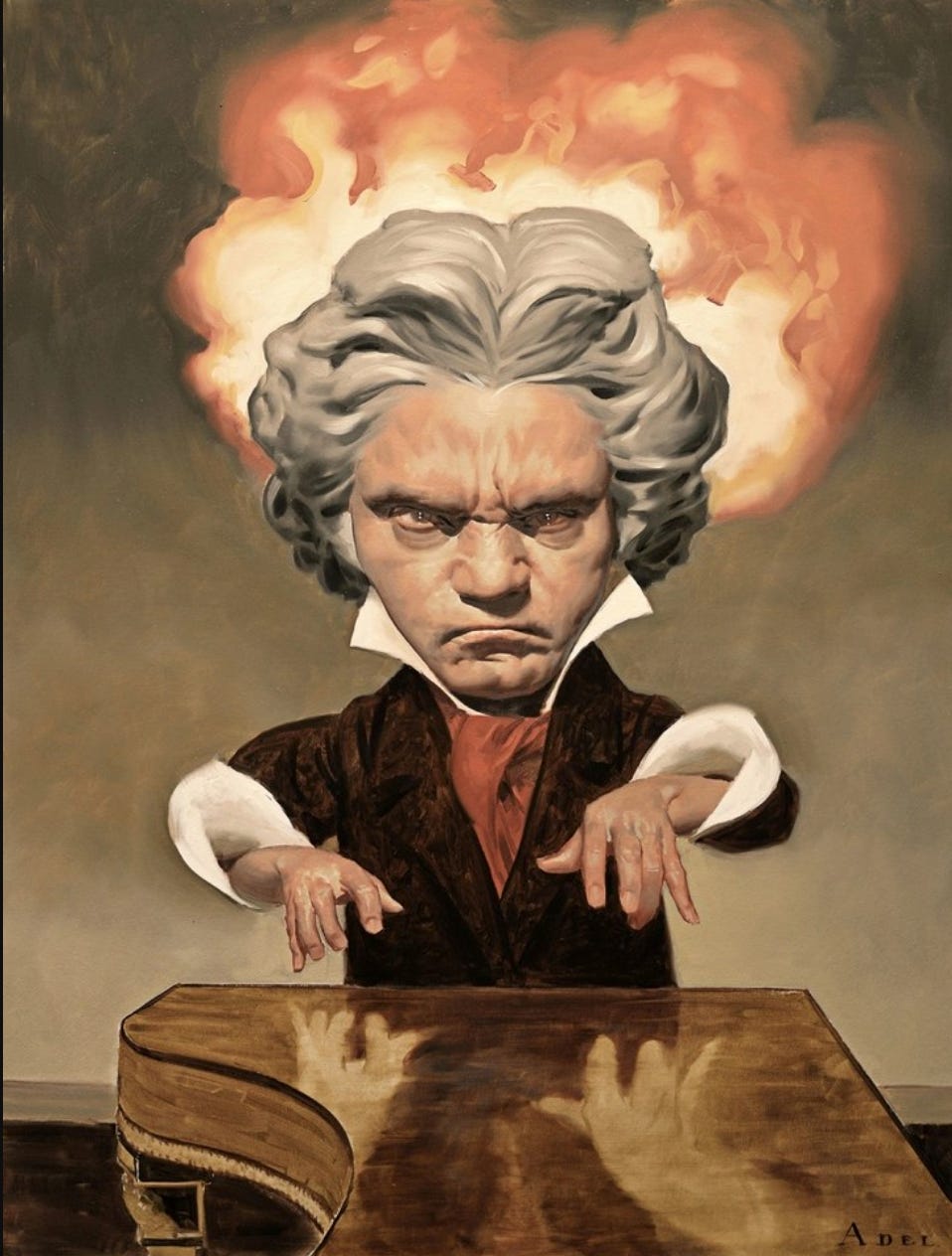

BEETHOVEN AND THE ACT

Stanley Kubrick was right when he used this movement as the music for his dystopian masterpiece A Clockwork Orange.

Welcome to the desert of the real!

If you expect smooth narratives or neatly packaged conclusions, you are in the wrong place. Here, we revel in the disquieting, the obscene, the paradoxical. In a world where ideology masquerades as truth, your decision to become a paid subscriber is not just a transaction, but an act of defiance against the superficiality that permeates our daily lives.

So, if you have the means and believe in paying for writing that enriches and disturbs, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

I’ll risk here an analysis of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, which will undoubtedly be dismissed as an eccentric exercise by the majority of the half-educated public. Let’s begin at the beginning because, in some sense, everything is decided in the first movement. A mysterious string tremolando breaks the silence and introduces a tension of expectation; then the stern motif 1, emerging out of the tremolando, gathers strength and strikes with all brutality. What cannot but strike the ear of a listener accustomed to classical style is the precipitous character of motif 1’s entrance in all its force: it happens too hastily—one would expect a slower development and ascent, but instead, we get a nervous self-overtaking.

To put it bluntly, Beethoven's music often verges on kitsch—suffice it to mention the over-repetitive exploitation of the “beautiful” main motif in the 1st movement of his Violin Concerto or the rather tasteless climactic moments of the Leonora 3 overture. How vulgar are these climactic moments in Leonora 3 (and Leonora 2, its even worse utterly boring version) compared with Mozart's overture to The Magic Flute, where Mozart still retains what one cannot but call a proper sense of musical decency, interrupting the melodic line before it reaches full orchestral climactic repetition and instead jumping directly to the final staccatos! Perhaps Beethoven himself sensed this, writing another final overture—the Op. 72c Fidelio—brief and concise, sharp, and the very opposite of Leonora 2 and 3. (The true pearl, however, is the undeservedly underestimated Leonora 1 Op. 138, whose very date is uncertain—it is Beethoven at his best, with a beautiful rise to a climax without any embarrassing excesses.) But at the beginning of Movement 1 of the 9th Symphony, Beethoven surpasses kitsch by bringing it to an extreme: the climactic repetition of motif 1 hits us preemptively with full force. The “dawn of Creation”? Maybe, but in the sense of Eric Frank Russell’s short science-fiction story “The Sole Solution,” which begins with the confused rambling of an old lone man:

“He brooded in darkness and there was no one else. Not a voice, not a whisper. Not the touch of a hand. Not the warmth of another heart. Darkness. Solitude. Eternal confinement where all was black and silent and nothing stirred. Imprisonment without prior condemnation. Punishment without sin. The unbearable that had to be borne unless some mode of escape could be devised. No hope of rescue from elsewhere. No sorrow or sympathy or pity in another soul, another mind.”

The old man then starts to dream about a solution:

“The easiest escape is via the imagination. One hangs in a straitjacket and flees the corporeal trap by adventuring in a dreamland of one’s own. But dreams are not enough. They are unreal and all too brief. The freedom to be gained must be genuine and of long duration. That meant he must make a stern reality out of dreams—a reality so contrived that it would persist for all time.”

After long hard work planning all the details, the time comes for action:

“The time was now. The experiment must begin. Leaning forward, he gazed into the dark and said, ‘Let there be light.’ And there was light.”

Here we reach the ultimate point-de-capiton (“quilting-point”): these last lines retroactively clarify that these ramblings are God’s thoughts just prior to creation. The beauty of this final reversal is that it turns around what would have been a standard version: that God’s thought process is revealed to be nothing more than delusional ramblings from a madman who thinks he is God... As we have already seen, for a philosopher this denouement is no surprise: that "the beginning is not at the beginning" is Schelling’s first lesson in his Ages of the World fragment, where he focuses precisely on what goes on before "the beginning."

The beginning of all beginnings is, of course, “In the beginning was the Word” from John; prior to this was nothing—that is, only divine eternity’s void. According to Schelling, however, eternity is not an undifferentiated mass—a lot takes place within it. Prior to "the Word," there exists a chaotic-psychotic universe of blind drives: their rotary motion and undifferentiated pulsating energy; and "the Beginning" occurs when "the Word" is pronounced—repressing and rejecting this self-enclosed circuit of drives into eternal Past. In short, at "the Beginning" proper stands a Resolution—an act of Decision—which differentiates past from present and resolves the preceding unbearable tension caused by these rotary drives. The true Beginning is thus marked by this passage from “closed” rotary motion to "open" progress, from drive to desire — or, in Lacanian terms, from the Real to the Symbolic. It is thus the decision, Ent-Scheidung, primordial Difference (from Old French, from Latin dēcīsiō, literally: a cutting off).

As is usual in sonata form, motif 1 is followed by motif 2, which announces a “lovely pastoral world,” a variation on the “Ode to Joy” melody from the last movement. The interplay of the two motifs is dazzling: about 7 minutes into the movement, motif 1 is rendered in a lyrical mode in G minor with added upper-neighbour semitones. It works as the opposite of its first climactic appearance in its pure violence. No wonder that, in contrast to this lyrical rendering, motif 2 appears in an increasingly brutal mode. One should at least mention how, due to its eerie background provided by a “mostly chromatic meandering in the bass,” the funeral march in the coda “grows to terrifying proportions, as a solemn procession for the dead becomes more like a macabre dance of the dead.” Here we encounter a typical Hegelian shift of “for” to “of,” of object to subject, since the subject itself gets caught in the movement. There is no sonata-form reconciliation at the end of Movement 1: it ends as abruptly as it begins — the final bars repeat a melodic line that could easily continue.

Movement 2 is supposed to render lively joy, but it does so with a touch of frantic madness — Stanley Kubrick was right when he used this movement as the music for his dystopian masterpiece A Clockwork Orange. Similarly, Movement 3 renders peaceful pleasure but with a touch of nostalgia and melancholy — it evokes a dream of a world as it was before the traumatic act of decision that strikes us in Movement 1. This brings us to the notorious Movement 4, which deceptively poses as the synthetic unity and step forward from the preceding three movements (the main motif of each is briefly recalled at the beginning). Some optimistic-spiritualist interpreters see in this movement nothing less than the disclosure of the “Meaning of Life.” They read the notorious Ode to Joy (recall that its melodic line is now the official anthem of the European Union) as part of a triad: Ode to Joy renders earthly brotherhood — brotherhood among men (it involves a strictly masculine standpoint: happiness includes “whoever has created an abiding friendship or has won a true and loving wife” — but what about wives' happiness?); then we pass into a “deeper” spiritual level, calling all brothers to “be embraced, millions” while looking up to a heavenly God — “there must be a loving Father” (in Grosse Fuge, Beethoven realized there is no such father); finally, the complex double fugue that concludes this triad stages an intermixture of both dimensions, which should somehow render life’s meaning — an earthly brotherhood grounded in awareness of a heavenly loving Father who protects us.

But this is not where Movement 4 ends. A careful listener can easily detect that something is missing from this recapitulation: Ode to Joy really ends after about 9 minutes when a prolonged weird silence is interrupted by Marcia Turca-style vulgar music that undermines brotherhood. Yes, all brothers are embraced — but those who cannot be must creep tearfully away from our circle. What if they are referred to not so much in words as through this vulgar music? The lyrics are: “Gladly, as His suns fly through heaven’s grand plan, go on your way joyfully like heroes toward victory.” But by then, the spell has already been broken. When after this rather creepy intermezzo, the Ode to Joy melody returns; it’s too late to cover up the crack. Then, as if acknowledging that brotherhood’s spell has been broken and only some higher transcendent agency can restore order, “Be embraced millions” enters again, enacting an appeal to God who must exist — “Brothers, above the starry canopy there must dwell a loving Father.”

At this point:

"Beethoven goes back to medieval sacred music tradition: he recalls a liturgical hymn, more specifically psalmody using the eighth mode of Gregorian chant. The religious questions are musically characterized by archaistic moments—veritable ‘Gregorian fossils’ inserted into a quasi-liturgical structure based on sequence: first versicle — response — second versicle — response — hymn. Beethoven's use of sacred music style attenuates the interrogative nature of prostration before the supreme being."

And then we get a double fugue as enforced reconciliation; what follows is fake — a hysterical mess lasting until the end of the movement. The true double fugue lies in Beethoven’s quartet movement Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 which — I agree with Daniel Chua — "speaks of failure, precisely opposite to triumphant synthesis associated with Beethovenian recapitulations."To summarize: The only moment of truth occurs in Movement 1; all other three movements enact different modes of fantasmatic escape: hysterically joyful violence (which literally reveals joyful brotherhood’s truth), escape into romantic nostalgia, and finally pathetic failure in Ode to Joy.

[1] Eric Frank Russell - Sole Solution.

[1] For a more detailed account of this topic, see the first part of Slavoj Zizek, The Indivisible Remainder, London: Verso Books 2007.

[1] Beethoven's 9th: the dawn of Creation!

[1] Lecture on Beethoven's Ninth Symphony (Part 1).

[1] Something similar happens at the beginning of the act III of Wagner’s Flying Dutchman: the chorus of Norwegian sailors provoking the ghosts on the Dutchman’s ship is overtaken and eclipsed by the phantom dance and eerie singing of the living dead, Dutchman’s crew.

[1] See Beethoven's Meaning of Life - The double fugue in the ninth symphony, in Enjoy Classical Music (Youtube) – this podcast induced the following comment: “Beethoven's 9th is the highest mountain of all music history, and the double fugue is its top peek.”

[1] Symphony No. 9 (Beethoven) - Wikipedia.

[1] Daniel K.L. Chua, The "Galitzin" Quartets of Beethoven, Princeton: Princeton University Press 1965, p. 240.

This piece was already analysed in a different way in Žižek's The Pervert's Guide to Ideology film from 2013, where he points out in length how many different political regimes from all parts of the political spectrum over different decades appropriated the 9th symphony as their own.

A different type of analysis from what I did in grad school. The most fascinating non performance related course I took was called, Beethoven and his use of the coda. A very long time ago. Great prof. I learned so much about his use and manipulation of sonata form and had a great time writing a paper in first movement of Opus 109. Through my analysis of it, I learned a great deal.